In looking at this situated context I hope to answer the focus question; Where does our understanding of cloud classification come from and how accurate is it?

Automated cloud classification exists within a network of agencies and organizations, instruments and data streams, and algorithm and models. It is my intention to investigate how the forces above lead to our understanding of clouds and inform cloud classification as well as how well the automated classification replicates human observations. While I do my very technical research, I will constantly ask myself about how the tools and algorithms I am using have led to these results.

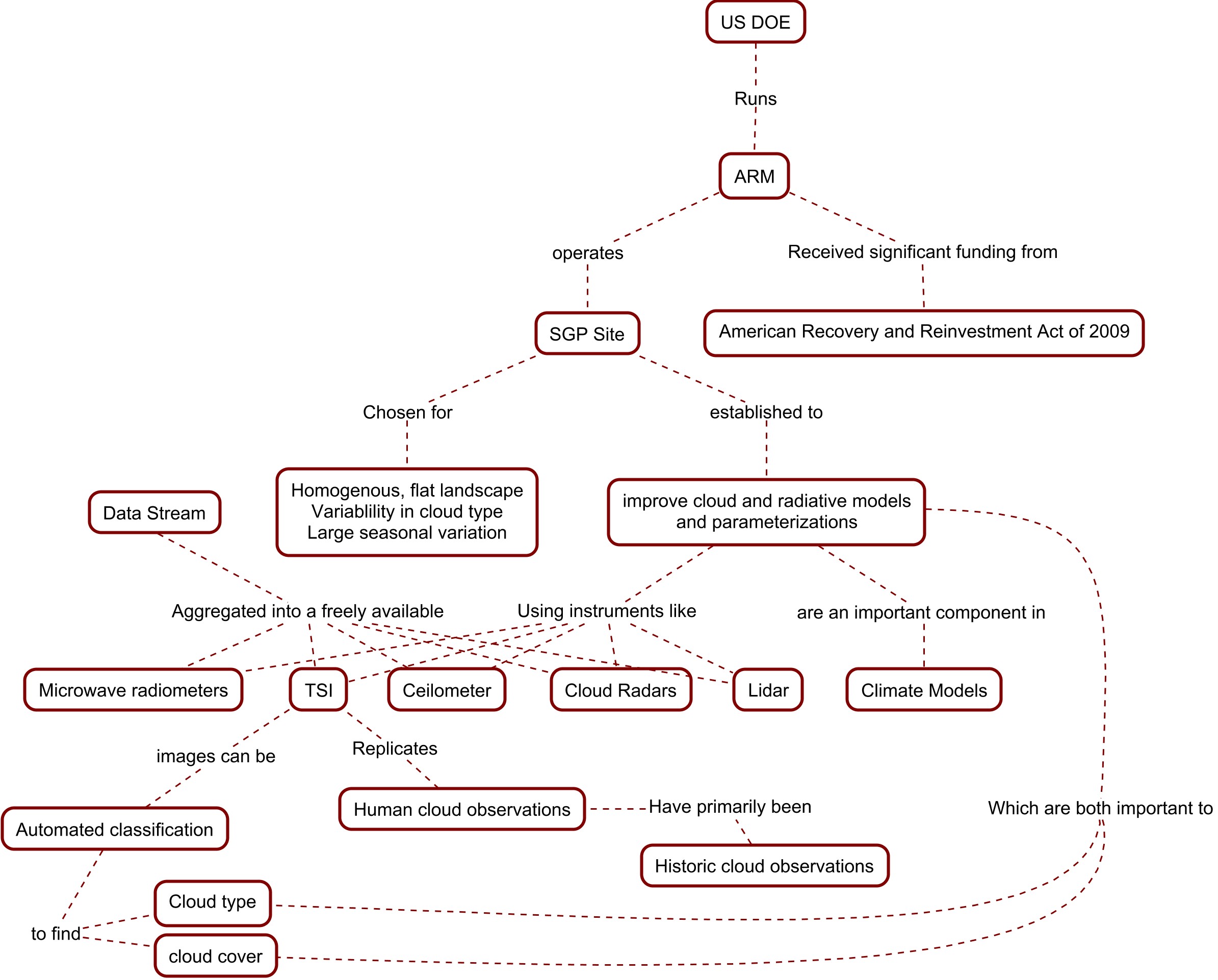

The Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) Program was established by the Department of Energy (DOE) to better understand the role clouds and radiation play in the climate of our atmosphere and earth. The undertaking was directly influenced by our need to improve climate models in order to better understand the causes and predict effects of climate change. This situated context is a current, specific instance of cloud classification and exemplifies our increasing reliance on technology to understand the natural world. There are many different forces at play in this example including funding sources and the politics of climate research, data sharing and processing, and the study of science and scientists. Below is a concept map of some of the dynamics at play in this specific example.

There are also many inter-organizational social networks that are apparent through scientific collaboration. Since there are any number of people working with the same data, instruments, or concepts there is the possibility for overlap and thus, collaboration. ARM is no exception. Looking at these scientific relationships is telling of how large scientific organizations conduct relevant research that has a practical application.

One way that ARM conducts atmospheric research which diverges from historic observations is through automated cloud classification, often from sky images. Cloud observations must be taken everyday and frequently throughout the day in order to have a comprehensive record that can be specific enough for day-to-day cloud forecasts or aggregated over the long term to see more climatic trends. This is simply not achievable with manual cloud observations. A number of different technologies are employed by ARM to view clouds, aerosols, and radiation in many different ways. The challenge using these instruments comes down to whether the instruments give us accurate and useful information, and if the data can be aggregated with historic manual observations to look at long term trends in cloudiness and different types of clouds.

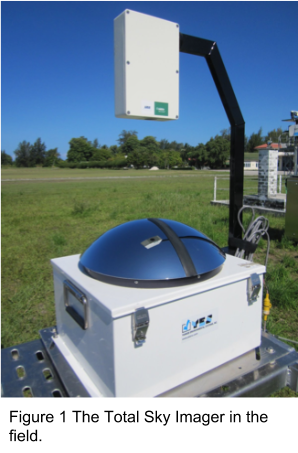

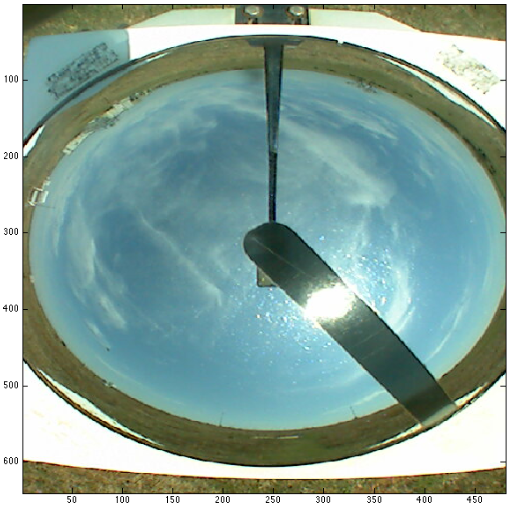

As discussed briefly in the Background section, Clouds play an important role in the climate of our atmosphere and earth. This is because clouds reflect incoming solar radiation, and absorb and re- emit terrestrial radiation. The occurrence and composition of clouds depends on local temperature, humidity and meteorological conditions as well as aerosol content. Unfortunately, there is still much we don’t know about cloud and aerosol interactions and cloud and so they contribute the most amount of uncertainty in climate models. Different cloud types have a different net heating effect on the atmosphere and surface, therefore it is important to be able to differentiate cloud types from observations. However, systematic ground observations of cloud type were largely discontinued in the mid-1990’s. Furthermore, there is often disagreement and discontinuity between observations depending on the instrument and location of observation. Since having a human observer is not feasible for a study that is global in nature, we must rely on cloud imaging devices which portray the sky like a human would view it. Although ARM maintains various instruments that monitor and observe clouds, aerosols, and radiation, an instrument called the Total Sky Imager (TSI) observes the sky closest to the way a human would.

emit terrestrial radiation. The occurrence and composition of clouds depends on local temperature, humidity and meteorological conditions as well as aerosol content. Unfortunately, there is still much we don’t know about cloud and aerosol interactions and cloud and so they contribute the most amount of uncertainty in climate models. Different cloud types have a different net heating effect on the atmosphere and surface, therefore it is important to be able to differentiate cloud types from observations. However, systematic ground observations of cloud type were largely discontinued in the mid-1990’s. Furthermore, there is often disagreement and discontinuity between observations depending on the instrument and location of observation. Since having a human observer is not feasible for a study that is global in nature, we must rely on cloud imaging devices which portray the sky like a human would view it. Although ARM maintains various instruments that monitor and observe clouds, aerosols, and radiation, an instrument called the Total Sky Imager (TSI) observes the sky closest to the way a human would.

The TSI is a camera pointed down at a hemispheric mirror that reflects the whole sky (Figure 1). While ARM has field stations worldwide, the Southern Great Plains (SGP) site near Lamont, Oklahoma, houses a TSI that has been taking photos of the sky every 30 seconds since July, 2000. These images can be automatically processed to give cloud cover and cloud type present. The “correctness” of the classification can be checked manually, although this present its own set of problems. This leads to an investigation of how to measure the validity of such cloud classifications.