Fukushima Daiichi: Japan's Resilience to Nuclear Plant Meltdown

Capstone 2017

Poster | Report

Summary | Annotated Bibliography

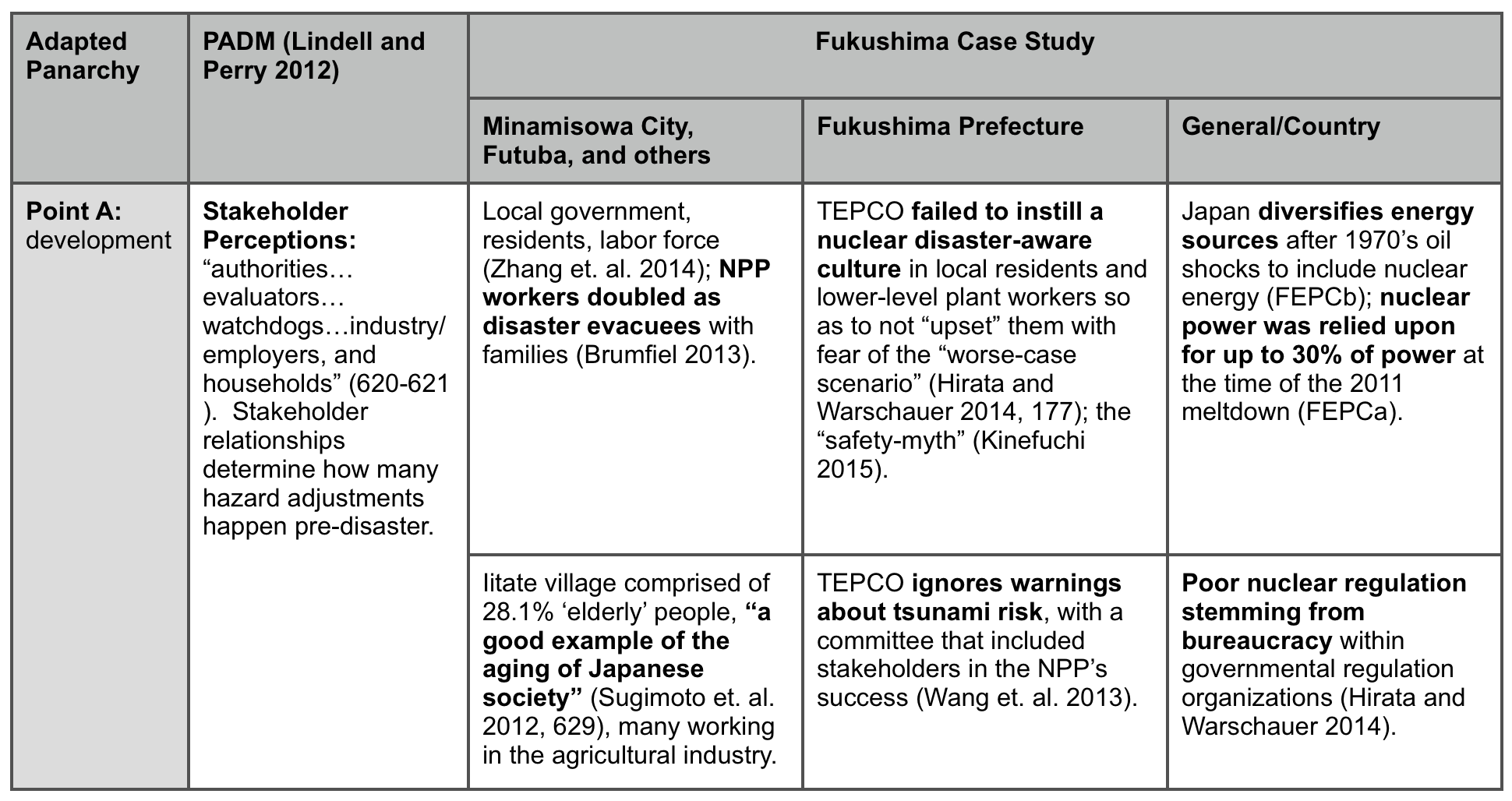

Nuclear energy has been a controversial topic for decades now. Predominant arguments for nuclear energy center around the lack of carbon emissions and the ability to produce mass amounts of stable electricity. Understanding the relationship between SES function and radiation hazard in our modern age is the dilemma that has led me to investigate the extent to which a country can be resilient to nuclear power plant disasters. In order to do so, disaster resilience must be reframed and reimagined in order to account for the distinct characteristics that occur in radiation crises across both space and time. In the context of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant meltdown, many authors have suggested that Japan’s resilience is based on a long history of earthquake culture. Rather than accept those theories at face value, I use adaptive cycles and the Protective Action Decision Model to analyze processes occurring at different scales of time and space within Japan.

Background

Resilience is a term used widely throughout academics and beyond. In my research, the most applicable definition of resilience is that used by Benson and Craig, in which resilience is a system’s capacity to undergo change while still maintaining function, and includes the ability to reorganize and learn (2014). Use of the theory is critiqued as being without “a direction or goal, and is often employed without reference to its subjects” (Bahadur and Tanner 2014, 202). Similarly, it is used as “a rhetorical devise with little influence on actual decision making” (Benson and Craig 2014, 780). In order to ground this study in a goal, specific subjects, and decision making, the case study is assessed by looking at social-ecological systems (SES) and disaster resilience.

SES resilience theory builds on the idea that “ecological resilience stimulates a community’s capacity to change, including complimentary changes within social resilience of that same community” (Kulig et. al. 2013, 759), and is even believed that the humans dominate the relationship (Walker et. al. 2004), making it important to idenify key actors in disasters. While humans have little control over the when, where, and what of a disaster, we still play a substantial role in the function of SES’s in the event and recovery stages. The role we play tends to revolve around traits such as capacity, vulnerability, hazard, and risk. In many cases, the resilience of an SES rides on how well the system is able to work around the constraints of such characteristics. This does not mean that vulnerability or hazard must be eliminated in order to have a successful disaster response, but rather “[it is] these characteristics of social–ecological systems (SESs) that will determine their ability to adapt to and benefit from change” (Walker et. al. 2004, para. 1).

In order to effectively study resilience to nuclear power plant disasters, the following two models are used:

Radiation Disasters

The SES and disaster response research addressed above is deeply rooted in our academic field already, but today’s ever changing technological advancements change the narrative of research. The reality of radiation disasters from nuclear plant accidents has changed the definition of disaster. The world was rocked by a nuclear power plant explosion for the first time in 1986 when a test at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant went wrong. The explosion caused airborne radioactive material to spread across parts of Europe and introduced the world to major implications of radiation accidents. These included the threat of thyroid cancer, as well as psychologic and physical impacts.

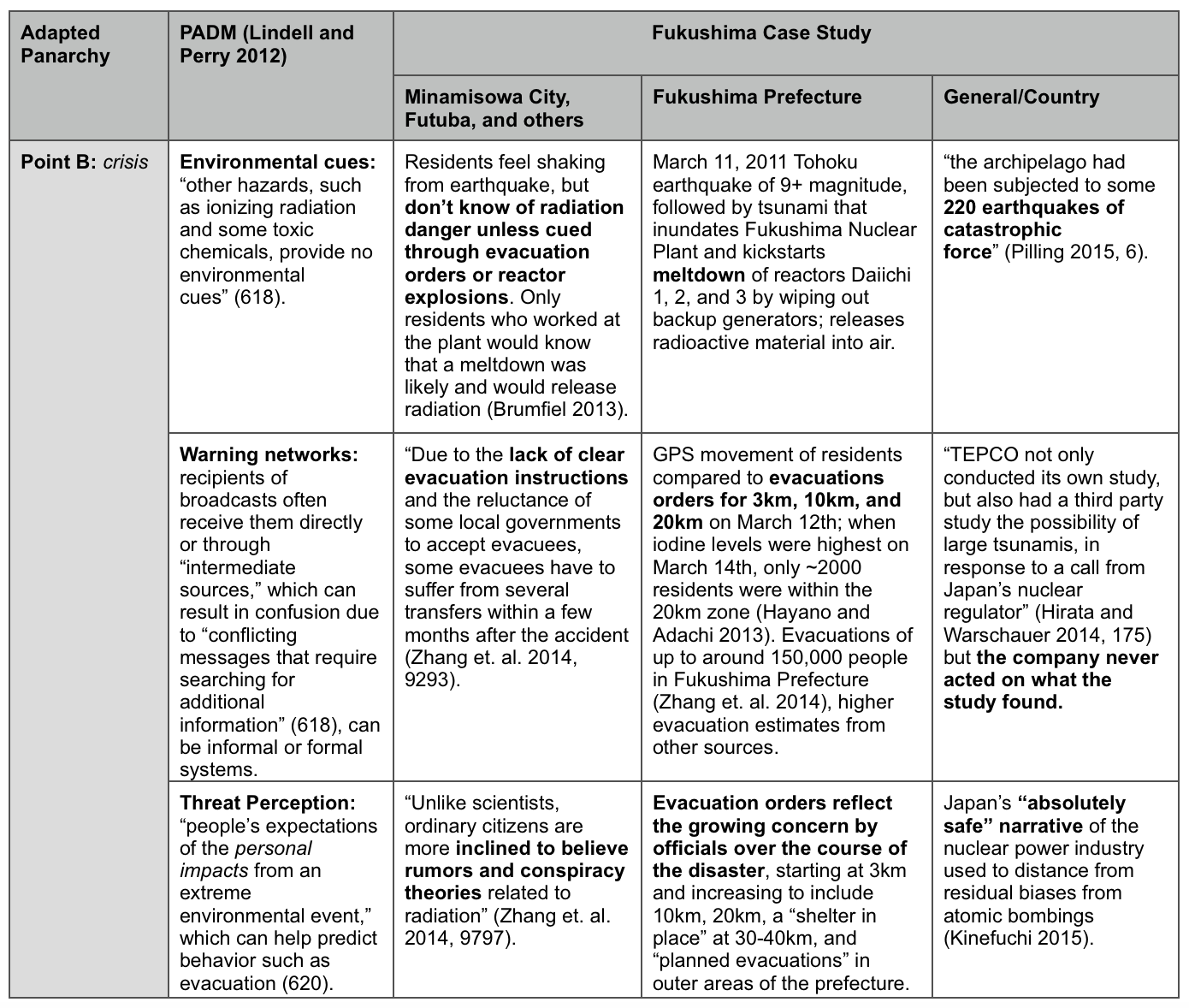

Radiation is not visible, and not well understood by the general public (Coleman et. al. 2013), making it both impossible for people to recognize environmental cues, and intrusive in psychological well-being (Lindell and Perry 2012). Chernobyl also taught us that radiation-contaminated resources like milk, food and land (Yamashita and Takamura 2015) create a link between the capacity of an individual and the responsibility of governmental bodies. Capacity and vulnerability link disaster events and a system’s resilience, in which the capacity refers to the resources “that people possess to resist, cope with and recover from disaster shocks they experience” (Wisner et. al. 2011, 28). While vulnerability refers to the “susceptibility to harm from exposure to stress” (Adger 2006, 268), it is important to remember that vulnerable parts of a system are not without capacity, but rather operate with a different capacity limit (Wisner et. al. 2011).

Fukushima, Japan

Before using Japan as a case study about disaster response, there are two major characteristics of the country that need to be examined first: the geographic significance and Japan’s aging population. Japan is an archipelago, meaning a collection of small islands, located at a specific point in the Pacific Ocean where four major tectonic plates meet (Karan 2009). As the plates grind together, they produce both minor and major earthquakes and tsunamis, recorded all throughout Japan's history. Such a history has created a culture of disaster in Japan, making emergency preparedness one of the nations top priorities (Karan 2009). A second urgent concern for the country is development. While Japan attempts to bolster its condensing cities full of a young, working generation, it is battling a steadily aging population (Karan 2009). The distribution of Japan's population has changed priorities in voting, economics, lifestyle, and more.

The Great Eastern Japan Earthquake

On March 11th of 2011, Japan experienced a 9+ magnitude earthquake just off the northeast Honshu coastline, in the Tohoku region. The area is home to the Fukushima Nuclear Power Plant (owned and operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company - TEPCO), located in Fukushima Prefecture. The Fukushima plant lost power after the earthquake produced a 15 meter tsunami, kickstarting Daiichi reactors 1, 2, and 3 into meltdown (Wang et. al. 2013). The meltdowns caused explosions, venting air full of radioactive material into the surrounding community and causing the evacuation of nearby residents (Wang et. al. 2013). In context, the explosions at Fukushima were rated a Level 7 on the International Nuclear and Radiological Event Scale, of which the accident at Chernobyl is the only other Level 7 designated event (Zhang et. al. 2014).

In a report after the accident, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) suggested that a major impediment to the functioning of the plant and surrounding areas before, during, and after the event was the assumption by stakeholders (including residents, local government, and TEPCO officials) in the region that the nuclear plant was safe enough that a disaster of such degree would never happen (WNA 2017a). This sentiment is supported by an article written by Etsuko Kinefuchi on the ‘articulations of Japan’s nuclear power hegemony’ (2015). Kinefuchi argues that the nuclear power program of Japan has gone hand-in-hand with narratives of nuclear plants as ‘absolutely safe,’ ‘green’, and ‘necessary for energy independence’ (2015). The IAEA claims this narrative was one of the factors that caused TEPCO to ignore up to five warnings about the plant’s tsunami risk (WNA 2017a), about which Wang et. al. states that 22 of the 35 stakeholders in a committee that suggested the warnings be re-evaluated “had ties to the nuclear power industry” (2013, 132). These re-evaluations of safety warnings resulted in changes to the plant’s safety design that ended up with a lower sea-wall than originally suggested.

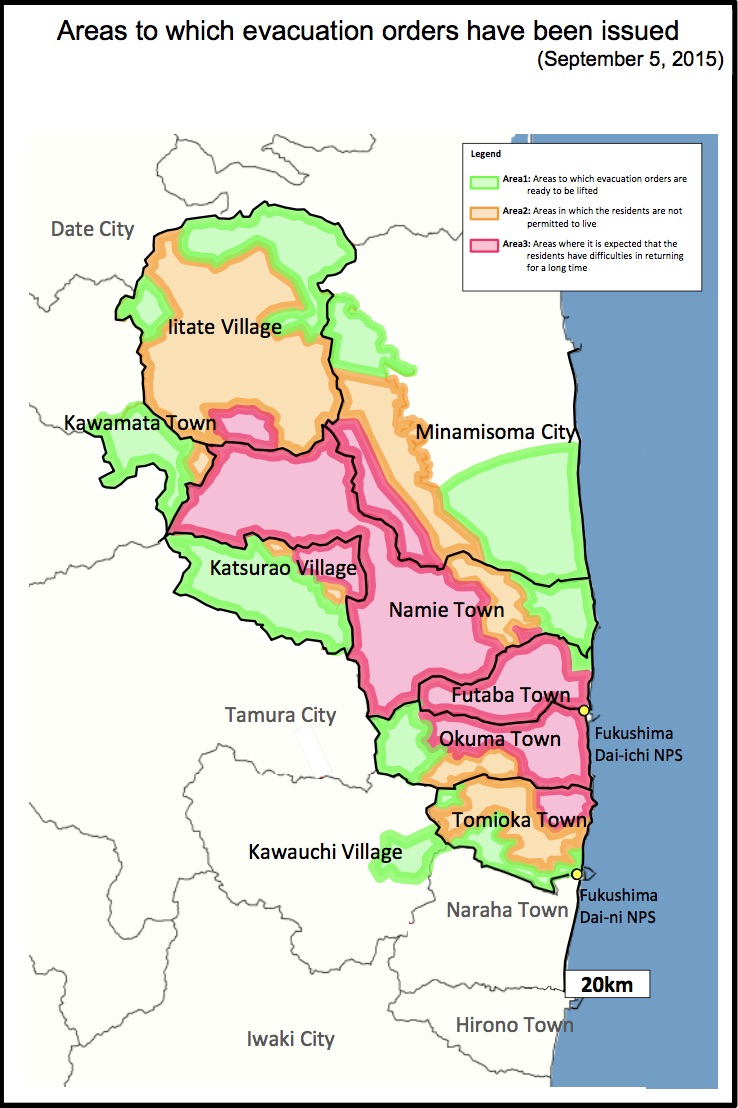

Evacuation

Immediately after the earthquake, concerns for residents spurred a number of official evacuation orders from March 12th, starting with residents living within three, ten, and then 20 kilometers from the plant (Hayano and Adachi 2013). All told, approximately 160,000 residents evacuated over the course of the accident (WNA 2017a), with only an estimated 2,000 people within the area when radiation levels were highest, on March 14th (Hayano and Adachi 2013).

The evacuation orders, while necessary to make sure that residents were safe from radiation harm, caused many problems of their own. Evacuations were rushed, with confusing and poor information available to residents, sending some evacuees on wild odysseys to find evacuation shelters (Zhang et. al. 2014) (Brumfield 2013). They can also be physically challenging for vulnerable populations, particularly older residents. Lastly, because of the characteristics of radiation many areas are still uninhabitable and around 120,000 people are still displaced (Iwasaki et. al. 2017).

Energy Consequences

Japan is a resource-poor country, importing most of its energy supply. During the county's transition from oil in the 1970's, nuclear power was framed as a ‘quasi-domestic’ resource, increasing energy security and providing green, clean energy sources (WNA 2017b) (Kinefuchi 2015), and by 2010 accounted for 30% of the country’s energy production (Koyama 2013). After the accident in 2011, trust in the use of nuclear energy plummeted. Public sentiment for a complete end to Japan's nuclear energy systems rose to just over 30% (Suzuki 2015). Shortly after the accident, plants began to shut down for safety checks, and eventually the last of Japan’s 50 nuclear power plants shut down in May of 2012 (Koyama 2013). Markets increased to liquid natural gas (LNG) instead, raising greenhouse gas emissions (Koyama 2013) so much so that the government began implementing feed-in-tariffs (or subsidies, if you will) for renewable energy. Plants began to reopen after nuclear was deemed still desirable by the Strategic Energy Plan, though only five plants are operating today (WNA 2017b).

Project Research

To what extent has Japan demonstrated resilience to the Fukushima Nuclear Plant meltdown?

Even operating under Benson and Craig’s most basic definition of resilience, in which a system undergoes change while maintaining function, Kulig et. al. point out that in order to effectively monitor any change in function there must be an element of “time” to the study. The study of resilience in the most complete sense of the word must bring together the specific with the general, the immediate with the future, and expectation with reality, all of which involve a multi-layered, multi-temporal scope.

On top of that, new technologies complicate how resilience is implemented. In order to better understand NPP disasters and the unique challenges they offer, I specifically situate my research in Japan, studying the extent to which the country demonstrated resilience to the Fukushima Nuclear Plant meltdown. I focus on the extent of demonstrated resilience rather than attempting to define a dichotomy of resilient or not. The approaches I take to answer this question are not meant to decisively measure the full range in resilience of any individual or community. Instead, they help conceptualize how countries manifest resilience at different scales in ways specific to radiation-centered disasters. As Fukushima is a nuclear disaster of remarkable scale, second only to Chernobyl, and has a unique set of event characteristics, this study will seek both a focused and broad understanding, without falling into a rigid dichotomy of resilience.

Exaggerating Adaptive Cycles

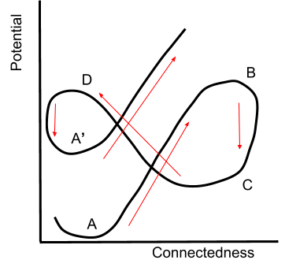

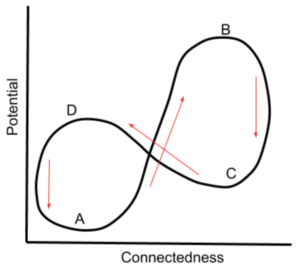

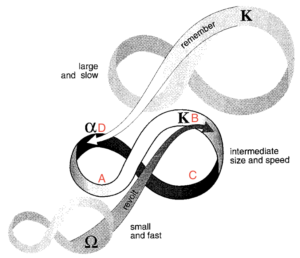

In order to contextualize radiation disasters like that of Fukushima in the larger framework of radiation  theory, I analyze the meltdown using adaptive cycles. Holling suggests that when an adaptive cycle completes the stages of growth, accumulation, restructuring, and renewal, the new cycle that emerges is different than the previous. I argue that when an SES experiences a radiation disaster, the difference between adaptive cycles is exaggerated due to the implications of radiation on time and space of recovery. The separation of point A from point A’ represents the exaggerated difference between the completed cycle (point A), and the upcoming cycle (point A’).

theory, I analyze the meltdown using adaptive cycles. Holling suggests that when an adaptive cycle completes the stages of growth, accumulation, restructuring, and renewal, the new cycle that emerges is different than the previous. I argue that when an SES experiences a radiation disaster, the difference between adaptive cycles is exaggerated due to the implications of radiation on time and space of recovery. The separation of point A from point A’ represents the exaggerated difference between the completed cycle (point A), and the upcoming cycle (point A’).

Point B translates to the onset of disaster in the cycle because it demonstrates a drop in system function from point B to point C. When the old cycle starting from point A is complete, the reimagining of the cycle into point A’ highlights the concept of remembering that occurs in a panarchy when a larger cycle interacts with a smaller cycle (seen in Figure 3). When applied to radiation disasters, the exaggeration of the cycle primarily suggests that if resilience to such a disaster is possible, it will present differently than it has in the past.

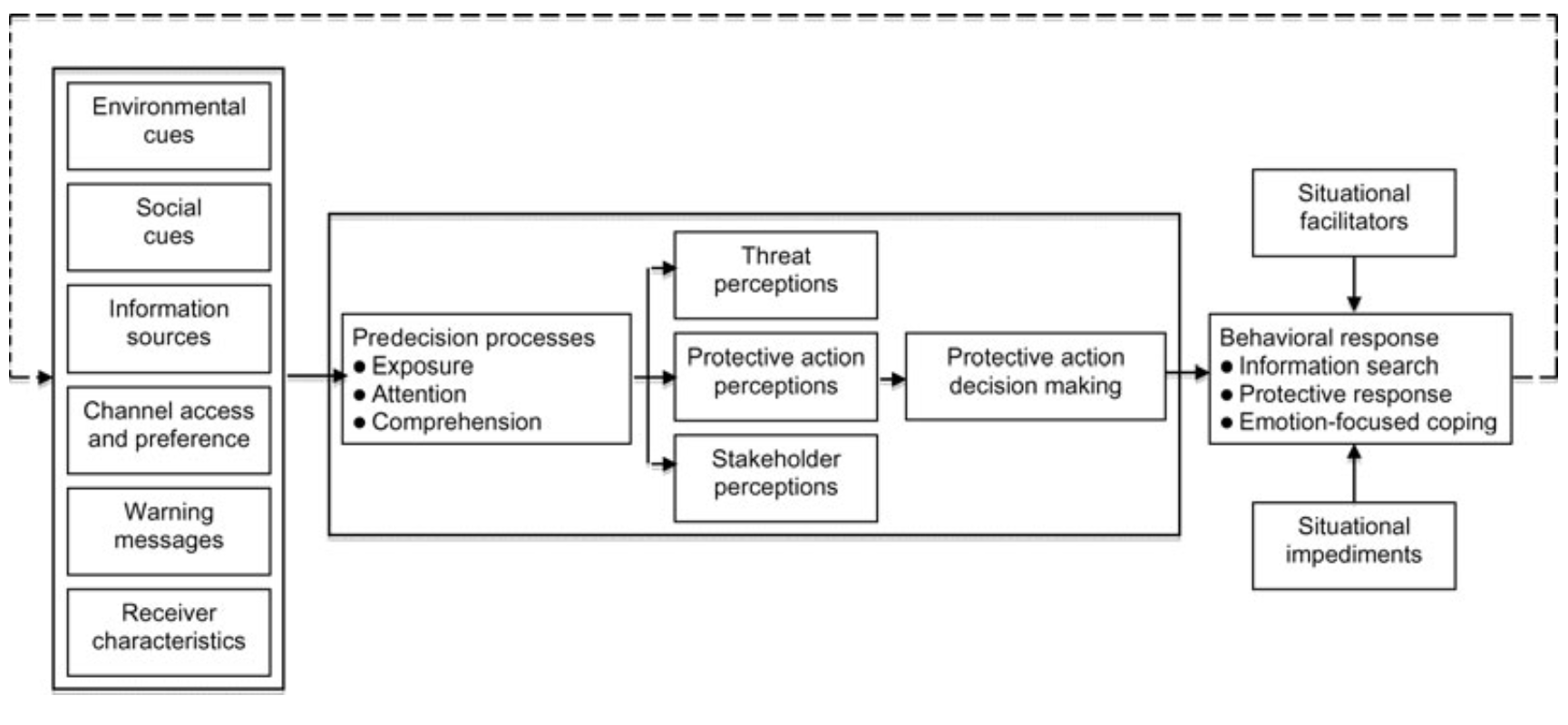

Using PADM

In order to thoroughly investigate this topic, the adaptive cycle model will be supported by the Protective Action Decision Model (PADM). This additional model will help distinguish between event characteristics at all stages of the crisis. The PADM model is helpful in studying Fukushima because it directly evaluates the “subjects of resilience" (Bahadur and Tanner 2014) by identifying contextual, psychological, and situational factors of resilience in Japan. The way PADM is used for this research involves first identifying key actors at different SES scales (e.g. local, prefectural, and national). From then on, events and actions by the actors are assessed at each stage of the crisis. As the SES goes through the stages of an adaptive cycle, certain parts of PADM are more prevalent than others. The sections PADM process occurs almost simultaneously, the adaptive cycle makes the role of each PADM component more or less influential at any given time.

The model’s typical application is described as being “situations in which emergency managers are transmitting information concurrently to large numbers of people who are responding to a single ‘focusing event’” (Lindell and Perry 2012, 625). Radiation disasters may have a “focusing event” that triggers exposure to radionuclides, but the crisis itself does not end at that event. Even if evacuees are safely moved, the stakeholders of the SES are still in a highly uncertain situation that requires planning for the future. PADM is typically not applied to disasters seven years after the event. However, because there is still radiation affecting both people and land in Japan, the model was still relevant to decisions being made at all scales of the country. Similarly, Japan is still home to nearly 49 other nuclear power plants at varying capacity. PADM can help the hazard-adjustments that are necessary moving forward to prepare the country for future disasters.

Studying Fukushima

In order to address the research question stated above, I use a collection of case studies, so to speak, that help sketch a full picture of the event at multiple scales. This includes studying the context from as small of a scope as an individual’s psychological state, to as large of a scope as governmental and industrial state. Evidence for these case studies comes from an array of different sources, including the more individual and community scale through health and wellness surveys, anecdotal evidence, migration patterns, communication, GPS data, and more. To expand outward, governmental regulation, energy implications, and cultural components are used to study community and country-wide scales.

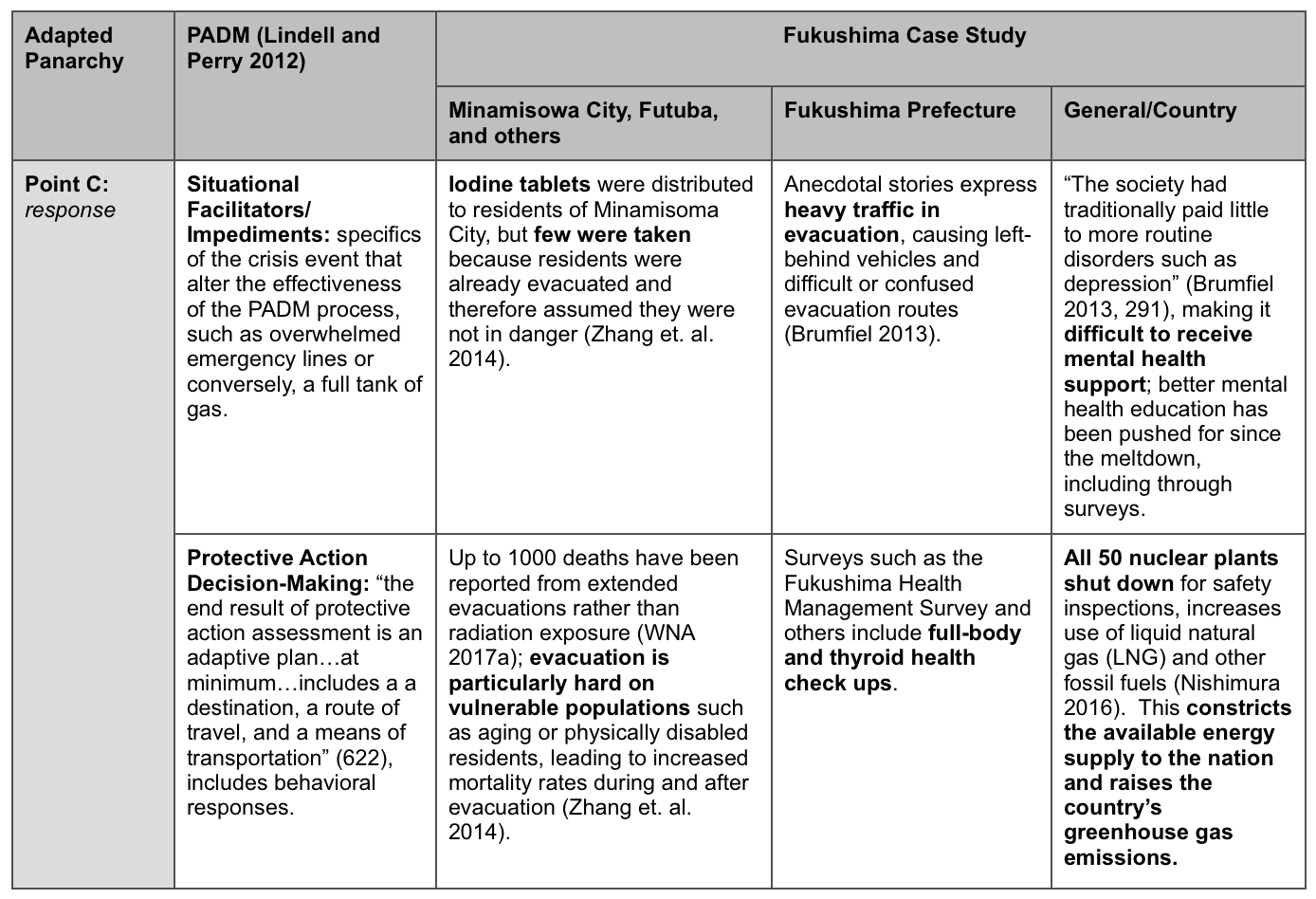

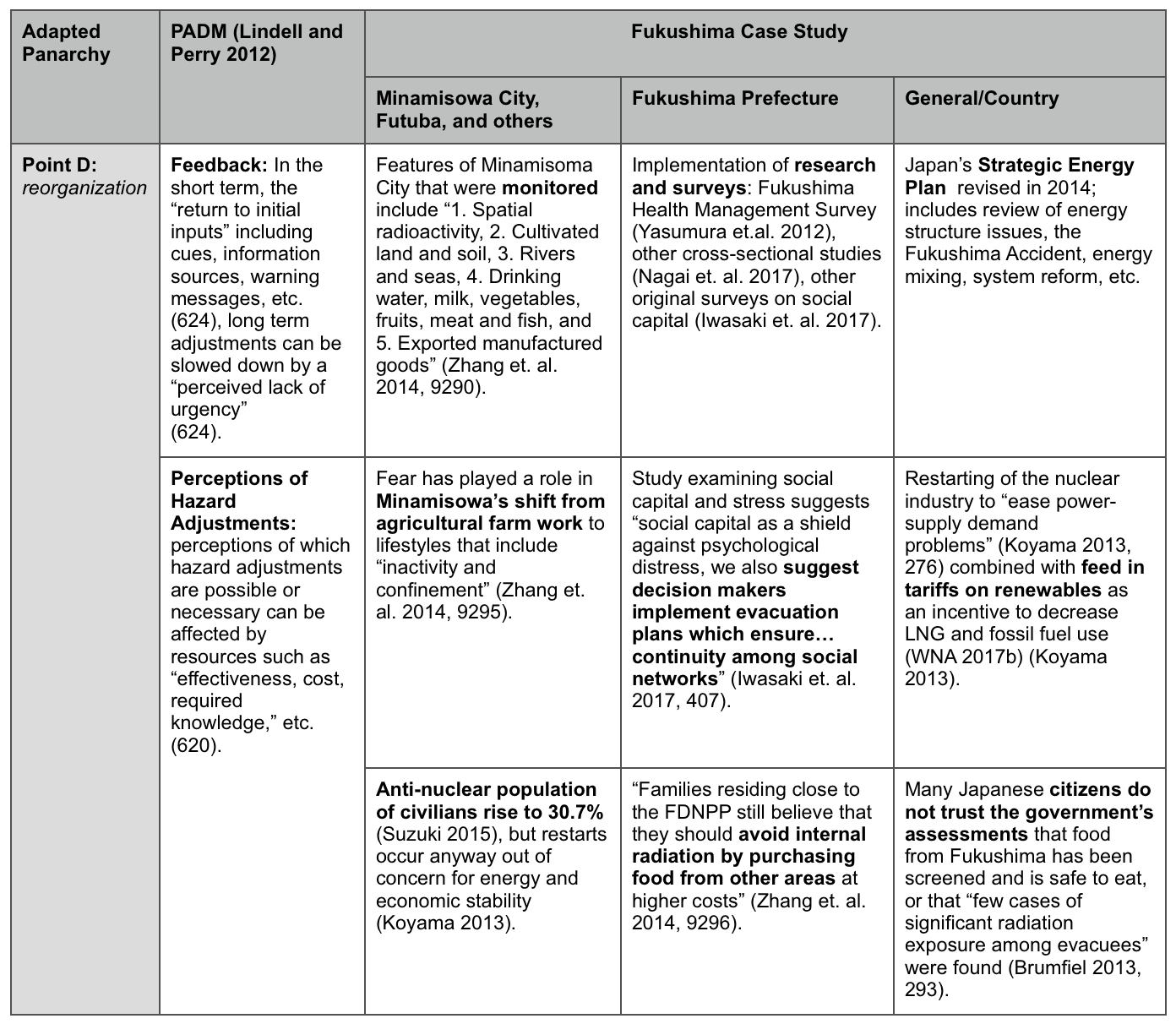

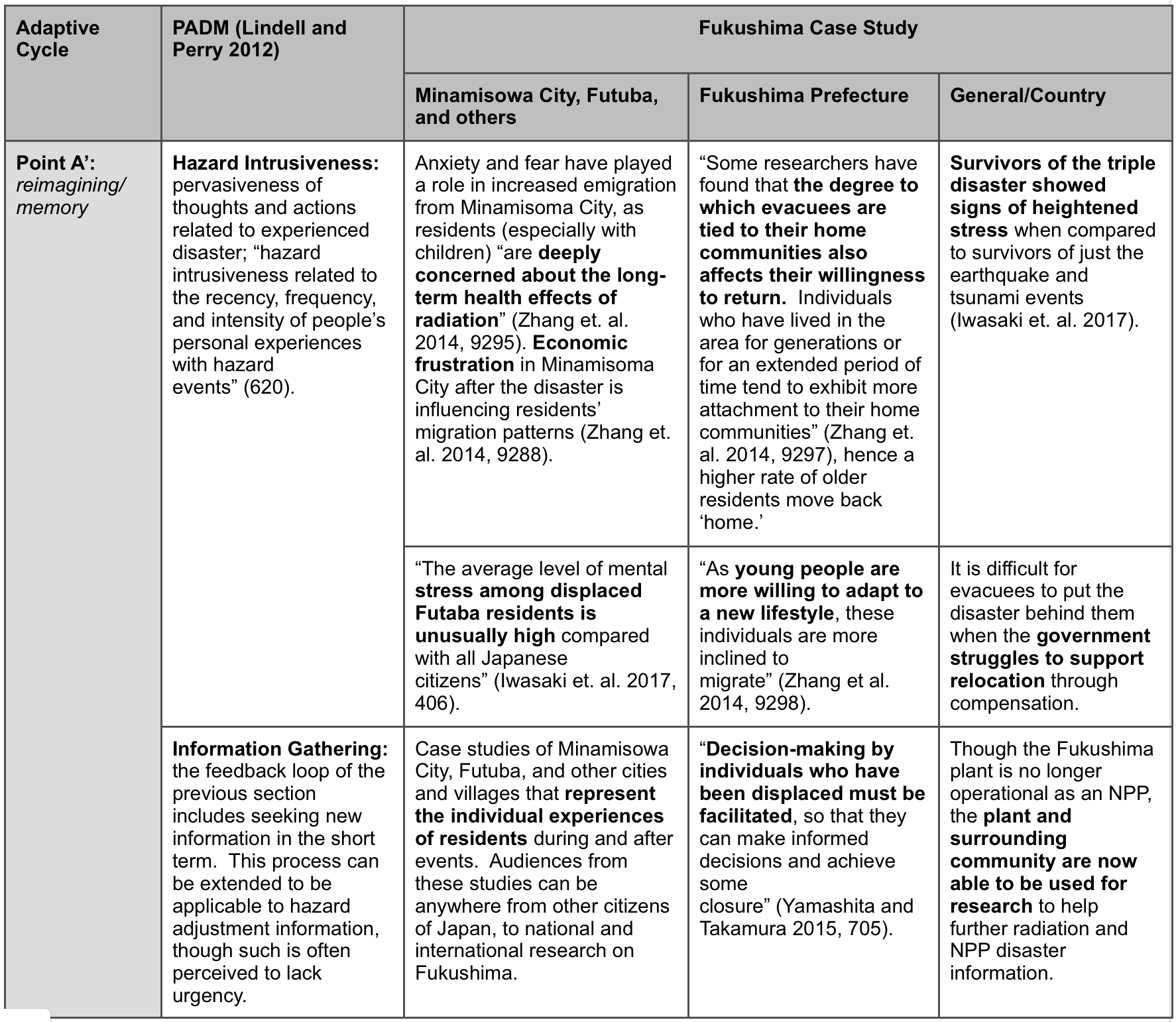

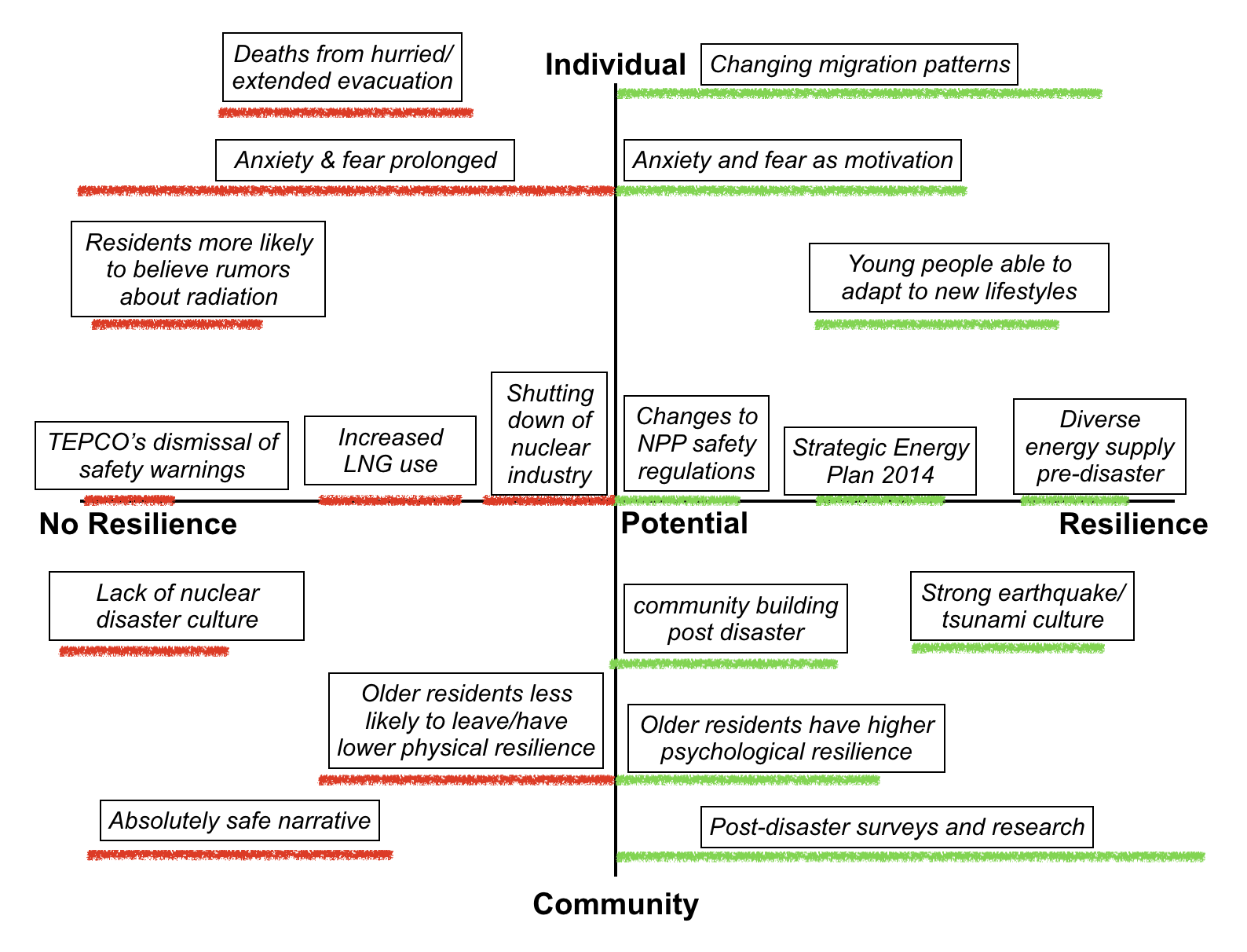

In order to effectively use the sources for this case study, evidence from each source will be organized by the points of the adaptive cycle model, as well as the corresponding parts of PADM. The results are displayed in a table format that includes the breakdown of the Fukushima case study into scale, so that the individual, community, and country-wide impacts are clearly defined. Finally, a chart is used to graphically represent overall important parts of the case study on a sliding scale of resilience. The chart uses stakeholder scale (individual versus community) and resilience potential to not only demonstrate whether or not resilience is present, but to also highlight the ranges at which it can exist.

Implications

Fukushima as the new Chernobyl

Though the compounded nature of an earthquake, tsunami, and NPP meltdown make the Fukushima events unique, exposure to radiation is not new. The Fukushima meltdown may be the most recent of large-scale radiation exposure, but perhaps the most notable of such disasters was the explosion at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant in 1986. Because Chernobyl happened so many years before Fukushima, the former accident was at an obsolete Soviet-designed power plant with 1980’s nuclear regulation, and a limited understand radiation hazards (WNA 2016). Fukushima was set in an extremely different context, but nonetheless utilized what was learned from Chernobyl. Radiation exposure at Chernobyl was compounded by lax regulation of contaminated food and milk. Mistakes made at Chernobyl were exacerbated by poor safety standards, but automatic shut-off regulations have improved greatly since then (WNA 2016). Finally, the clean-up processes at Chernobyl put thousands of lives at risk (WNA 2016).

Other research on the Chernobyl incident suggests that there are still largely place-based differences that impeded more successful disaster resilience. While Japan is still reeling with traumatized citizens, it has not been dealing with the extent of political upheaval and corruption that Chernobyl was experiencing in the 1980s. When speaking of radiation research, Adriana Petryna mentions that “the Belarussian government has tended to suppress or ignore scientific research; it downplays the extent of the disaster and fails to provide enough funds for the medical surveillance of nearly two million people who live in contaminated areas” (2002, 5). Similarly, when the Soviet Union had sovereignty over the area immediately after the accident, the government set higher radiation threshold limits that allowed them to escape “key ethical questions about the health effects of Chernobyl” (Petryna 2002, 50). The discrepancies between public information and private government research contributed to increased tensions between stakeholders in Chernobyl.

Even now, only seven years after Fukushima, Chernobyl is decades farther into a recovery that will take decades more, and research comparing the two events continues to be produced. If Fukushima and Chernobyl can tell the world anything, it is that although such disasters will likely be uncommon, they are possible. By acknowledging that there are still hazards from NPPs, more countries around the world may begin reacting accordingly.

Other Technological Disasters

As mentioned, Japan’s experience of the triple disaster is quite unique. Not only is it unprecedented in complexity of disaster, but the nuclear plant explosions themselves are second only to Chernobyl in intensity and scope. The Bhopal disaster in India in 1984, right before Chernobyl, is likely one of the most closely related technologic disasters after Chernobyl. Though it did not result in longterm relocation of residents, it did supersede both nuclear disasters in casualties, and rivals in the realms of fear, loss of trust, and implications of disaster research. Sheila Jasanoff has written extensively about the Bhopal disaster - in particular about the “right to know” and the role of the law in aftermath. She highlights the “asymmetries of power - between the state and the corporation on one side and the gas affected people on the other” (2008, 684) that were the driving forces behind the event’s main complications. In the evolving nature of NPP disaster response, the asymmetries of power and agency between stakeholders seems to connect the contexts of Fukushima, Chernobyl, and Bhopal.

Additionally, keeping all scales of an SES accountable is a concern for any disaster. This is complicated because of undefined expectations of the technology sector in terms of accountability, as Jasanoff mentions in her 2008 paper on Bhopal. Jasanoff write, “most modern regulatory systems place on the producers of hazardous substances, such as industrial chemicals, the burden of generating and disclosing information about the characteristics of their products…in effect, a huge, uncontrolled field experiment was conducted on unsuspecting human subjects” (2008, 684). In order to demand accountability, appeals for change must come from all levels of a context. By themselves, individuals in Bophal likely do not have enough political power to incite change. Leaving it up to the government alone, however, would likely result in even less accountability.

What Chernobyl, Bhopal, and Fukushima all share is a set of stakeholders with different priorities. Tensions between stakeholders are present in most disasters, but radiation and the broader genre of technological disasters have a unique relationship with humans. Humans build NPPs, run them, and then try to fix them when there are accidents. The question of blame is something that is so tumultuous that it aggravates relationships between stakeholders even more. By acknowledging the role of each stakeholder in a system, there is less ambiguity about why decisions are made.

Learning from the Past, Internationally

Fukushima provides a great recent case study through which to understand resilience to nuclear plant meltdowns, but it still begs the question of whether the consequences of what happened are accessible enough by the larger international community to make appropriate changes. Can any country be resilient to nuclear plant disasters? Already, the implications of the meltdown have spread to other countries. Germany and Switzerland have declared that they are planning to phase-out nuclear energy, regardless that leading nuclear disaster authors like Wang et. al. suggested that “these decisions would not only cost millions of dollars but also [leave] the countries struggling to find alternatives to meet the gap of electricity supplies” (2013, 127).

Beyond just political decision making, citizens in countries that already have an established nuclear energy sector, like China, have changed their perceptions of risk since the accident. Huang et. al. surveyed residents living near nuclear plants in China and found that risk perception had shifted from “limited risk” to “great risk” (2013). Researchers have already found that intrusiveness can be linked to future disaster responses; “researchers have found a positive relationship between level of threat belief and disaster response across a wide range of disaster agents, including floods,…earthquakes, and nuclear power plant emergencies” (Lindell and Perry 2012, 621).

When considering if any country can be resilient to NPP disasters, it seems reasonable to at least conclude that the potential to present resilient-like characteristics is possible. France, for example, has an even higher dependence on nuclear energy than Japan, with roughly 75% of energy generation coming from nuclear (WNA 2018). Given that France now has two different NPP disasters to learn from (with extremely different levels of successful response), as well as a strong culture of reliance on the energy source, France has the right incentives to prepare for such disaster. That being said, there is still a lot to understand before the word ‘resilience’ should be applied to a radiation disaster with any confidence.

Next Steps

Like any disaster, an NPP meltdown is above all else a shock to an SES system, inherently disrupting function. Preparedness can go a long way in creating a system with effective disaster response, seen over and over again through earthquake and fire drills, and the like. Though not a guarantee, simple disaster preparedness is one of the many ways governments across the world have responded to devastating events. Table 1 showed us that before the events at Fukushima, TEPCO intentionally left nearby citizens in the dark on possible hazards, for fear of suggesting a “worst case scenario” (Hirata and Warschauer 2014, 177). Since then, the Japanese government has recognized the need to instill stronger NPP disaster preparedness in both its power plants, and its people. The Japan Atomic Energy Agency, or JAEA, started running disaster drills at NPPs in 2016, with a total of four drills completed (JAEA 2018). The implementation of this policy since the Fukushima disaster solidifies the argument made in previous sections of this paper about the speed at which Japan has the potential to create resilience on a national scale.

Disaster drills are not enough to build resilience to radiation disasters, however. Such disasters have thus far demonstrated such pervasive consequences that more fundamental changes must be made to Japan’s NPP disaster preparedness endeavors. Assumptions that it is possible to maintain a steady-state by many policies, like those encouraged through sustainability models, encourages approaches to disasters that will eventually fail. Attempting to control a system or cycle in the event of a disaster ultimately results in failure to function. As an alternative, I suggest reexamining the theoretical objectives of disaster preparedness policy.

When suggesting to reexamine such policy, I can not pretend to have the answers. Instead, I suggest that future policy in Japan must be crafted while keeping in mind that in the face of disaster, policy will not be foolproof. A goal should be to create policy that is likely not perfect when all hell breaks loose, but does not completely fail either. Adaptive cycles utilize a lot of the same theoretical principles I suggest here, encouraging change and adaptation. At point B in an adaptive cycle, where disasters occur, the number of possible futures for the cycle is high (via the axis “potential”). With so many possible futures, both good and bad, policies that focus on a part of the adaptive cycle with such a high scale of potential must acknowledge that the outcome of the cycle cannot be predicted.

Further Research

Adaptive-cycle thinking can be implemented in more than just policy renovations. Disaster research as a whole can be expanded to ask more questions about the relationship between adaptive cycle and disasters. The study of radiation disasters in particular must be continued throughout our lifetime in order to fully understand events like Chernobyl and Fukushima. As that research unfolds, more and more factors will create futures for each context that we won’t be able to predict.

My research has been limited by a number of things. The largest impediment, however, has been time. In the last seven years, so much has been accomplished in rehabilitating and supporting the community and land of Fukushima, with so much more left to do. On top of that, Japan’s government has proposed all sorts of policy changes that have yet to be mentioned in this paper because it is difficult to assess their success yet. By repeating the questions from this research over the next fifty or one hundred years, we will get closer to a more complete understanding of radiation disasters. Chernobyl has already shown us that a lot can happen in thirty years, and yet the world still lacks the basic information necessary to respond to similar disasters accordingly.

The larger purpose of this study has been to understand the extent to which resilience can be attained. A critical assumption to question and build upon would be whether or not resilience is even the correct theory to be using. I do not necessarily imply that there is a better word already out there, but Fukushima sets the stage as an opportunity to develop new theoretical groundwork on disaster response. If this were the case, the research suggest for others would question a few basic assumptions of resilience: can there be adaptation without resilience? Is resilience always a good thing? Can you be resilient while also dependent? My research often involved using resilience definitions as a yardstick for what could be accomplished in a system. I encourage other researchers to question whether or not the yardstick itself is what needs to be changed.

References

To read more about each of these resources, check out my Annotated Bibliography page.

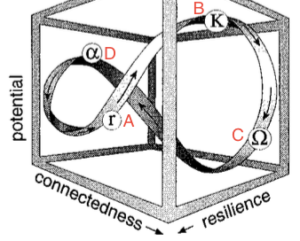

set of adaptive cycles at multiple scales of time and space.

set of adaptive cycles at multiple scales of time and space. Holling’s original 2001 article include a third dimension that specifically refers to resilience. Using the third dimension, his model twists backward between points B and C and forward between points D and A, the forward movement representing increased potential for resilience.

Holling’s original 2001 article include a third dimension that specifically refers to resilience. Using the third dimension, his model twists backward between points B and C and forward between points D and A, the forward movement representing increased potential for resilience. community suddenly decide to take a stand against plastic bag use by bringing reusable grocery bags while shopping.

community suddenly decide to take a stand against plastic bag use by bringing reusable grocery bags while shopping. While a panarchy addresses overarching system changes, PADM can provide a platform to dig deeper into disaster response circumstances, which can bolster or alter the outcome of a panarchy in practice.

While a panarchy addresses overarching system changes, PADM can provide a platform to dig deeper into disaster response circumstances, which can bolster or alter the outcome of a panarchy in practice.

I found evidence of adaptive cycles at each scale of SES within Japan.

I found evidence of adaptive cycles at each scale of SES within Japan.