At the top of a mile-long staircase I stood at Evans lookout in the Blue Mountains and stared at the edge of the world. Beyond a few eucalyptus trees I saw nothing but mist. We are at the edge of the world in a quite literal sense. To get here we time-traveled over Friday, January 9th and crossed the world’s largest ocean. The constellations are entirely new. Instead of birds, bats flock to our rooftop at dusk.

Bats are the mildest creatures in a land at home with danger. The continent plays host to 11 of the world’s most venomous snakes, poisonous spiders, largest saltwater crocodiles, great white sharks, and heart-stopping box jellyfish. Australians seem to think this is all great fun. A bus driver told us about a Navy diver repairing the underside of a battleship when a bull shark attacked him. He lost a limb or two, but after undergoing years of therapy, he “got over it.” A professor warned us that the sting of a venomous Irukandji jellyfish would cause “some discomfort.” A zoologist explained, in a bright and cheery tone, that a kangaroo’s middle toe could disembowel us. We learned to lie down and relax after suffering a snake bite. Snake venom attacks the lymphatic system, so running away and panicking and waving to your friends for help makes it worse. In short, danger is only a big deal here if you make it one.

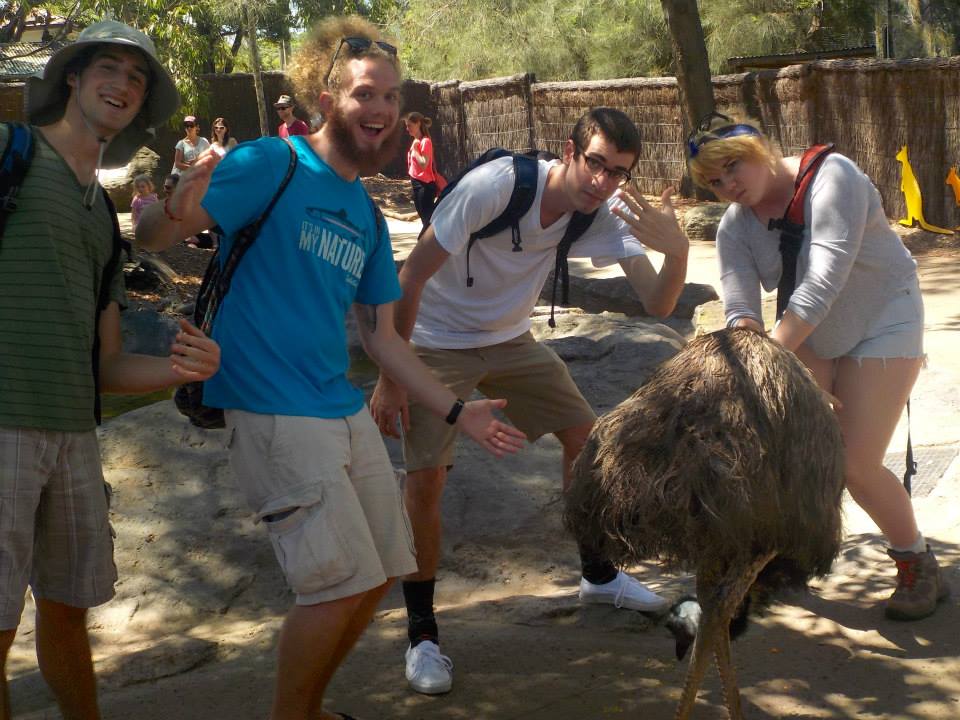

So far, I’ve spotted a lizard, countless geckos, a water dragon, a tortoise, and a platypus. At the zoo, we played with an echidna (a porcupine-shaped monotreme that behaves a bit like a stoned philosophy major). It can even dream and formulate abstract thoughts. As it lumbered toward me, I pictured it saying, “Hey man, last night I had this dream…”

Our encounters with Australia’s legendary arachnids include a neon green spider with white stripes, a few golden orb weavers, a huntsman that hangs out in the boy’s hallway, and a zoo-owned redback locked in a supermax glass-tubed prison. Upon seeing a spider the best thing to do is nothing. Just freeze. They only bite if forced to.

Until 1964, Australians refused to acknowledge a people they thought of as just another animal, the Aboriginal. Ever since Indigenous people were removed from the government’s flora and fauna list, white coastal-dwelling Australians know little of Aboriginal history or customs. During one initiation ceremony for boys of an Aboriginal community, a white female police officer barreled through Aboriginal land and disrupted the ceremony. The tribe received no reparations besides a few words of apology. Most sites where white settlers massacred Aboriginals remain unmarked.

White people have waged a fanatical campaign to turn Australia’s natural environment into England’s, in thought if not in form, since they arrived. A panoramic oil painting at the Hyde Park Barracks shows Sydney Bay looking like the English countryside adorned with lush backyards and Victorian architecture. It turns out that the painting was an early tourist brochure meant to draw settlers to Australia by reminding them of home. Even today modern-day Australians have yet to make peace with the first inhabitants of the continent.