Now that independent research week has come to an end, we have reconvened as a single unit, but we are not simply picking up where we left off. We have relocated from New South Wales to Queensland, from Sydney to Brisbane, from a residence hall to homes. The conversations before and after the lectures are filled with references to homestay “mums” and dads, brothers and sisters, and grandparents and pets. The students compare notes on neighborhoods and suburbs, and barbecues and “footy” outings. They measure their new experiences against their preconceptions about Australian families. Most of all, they tell stories because, as any viewer of Modern Family knows, families are a rich source of comedy and drama.

Meanwhile, I have moved into a West End apartment across from Musgrave Park with my husband, daughter, and son, where we have been taking a turn playing at Australian family life. In spite of our best efforts to search out authentically Australian experiences, recently, we have found ourselves replicating many aspects of our Portland routines. Oliver spends three days a week at an Australian preschool. Celia takes the train to a ballet studio. I head off to class in the morning, and John is pursuing his sabbatical research. Before breakfast, we fend off (or give into) Oliver’s requests for “just one more” episode of the Octonauts, an animated show about a team of scuba-diving animal and “vegimal” super heroes. After dinner, we help Celia with her homework and fend off (and refuse to give into) her requests to FaceTime the family cat. I have settled on a running route and mastered the local farmer’s market schedule. John has found a neighborhood pool and learned to translate Australian coffee menus. (N.B. There is virtually no drip coffee in Australia. Coffee is either instant or a variation on espresso. John orders a “long black with a dash of milk.” I prefer a “flat white.” Iced coffee comes with a scoop of ice cream, and, incidentally, so do pancakes!)

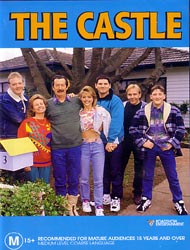

But our ideas about Australian family life are not exclusively anecdotal and cross-cultural. This week, the students and I heard a lecture on Australian families. We also screened the fabulously funny 1997 Australian movie The Castle. In the evenings, I have been reading Tim Winton’s celebrated 1991 novel, Cloudstreet. What emerges from this constellation of academic discourse, film, and fiction is a more complicated and shifting picture. As we have been learning in class, family occupies an absolutely central place in the Australian cultural imaginary. It is no surprise that a nation of people anxious to distance themselves from their primarily male and convict origins would come to enshrine home and family. Neither is it surprising that many post-War Australians would elevate home ownership to an important expression of the national dream. Despite this robust reverence for traditional notions of family and home, current Australians have had to come to grips with countervailing statistics about the country’s declining fertility rates and growing house price-to-income ratios. They have also been confronted with disturbing counternarratives about government policies of Aboriginal child removal and their own toleration for domestic violence.

What makes The Castle so delightful is the way it manages to translate the positive historical myths into comedy. The loving, but hapless, blue-collar Kerrigan family buys a home next to an airport runway and beneath a network of high-voltage power lines and sets to work “improving” their castle with hopelessly kitschy decorating schemes and thrifty additions. When the airport makes plans to expand, the Kerrigan family decides to fight the “compulsory acquisition” of their home. As Darryl, the family patriarch says, “I don’t want to be compensated. You can’t buy what I’ve got.” A hilarious court battle ensues, and, in the end, family pride and loyalty defeat corporate greed.

Winton’s novel is Australian history as family saga. It traces the stories of the working-class Lamb and Pickle families who share the same capacious ruin of a house on Cloudstreet in Perth between 1943 and 1963, from the aftermath of WWII to the crime spree of the “Nedlands Monster.” Each family is fleeing its own tragedy. The Lambs respond with work and religion, and the Pickles resort to gambling and drink, but the real subject of the novel is family itself. This novel seems to hold the same place in Australian literary history that Huck Finn occupies in our own canon. Critics enthuse about the power of Cloudstreet to evoke the colloquial language and natural landscapes of Australia.

Literature does not, however, just reflect preexisting ideas about nation; it helps to create and popularize those ideas. Educators here have made Cloudstreet so central to the high school curriculum that a generation of students have come of age understanding Australian national identity according to Winton’s representations of family life. The novel begins and ends with a family picnic. These are the opening sentences: “Will you look at us by the river! The whole restless mob of us on spread blankets in the dreamy briny sunshine skylarking and chiacking about for one day, one clear, clean, sweet day in a good world in the midst of our living.” As you can see, Cloudstreet is compelling. I hope that I have you hooked.