America’s prison problem is no secret. Our share of the world’s incarcerated population is grossly disproportionate to our share of the world’s total population: the NAACP reports the percentages to be 25% and 5%, respectively. Tragically, the percentage of those incarcerated who are people of color is also grossly disproportionate to the percentage of the total population of the United States of America who are people of color: the NAACP reports the percentages at 58% and 24%, respectively.

America’s prison problem is no secret. Our share of the world’s incarcerated population is grossly disproportionate to our share of the world’s total population: the NAACP reports the percentages to be 25% and 5%, respectively. Tragically, the percentage of those incarcerated who are people of color is also grossly disproportionate to the percentage of the total population of the United States of America who are people of color: the NAACP reports the percentages at 58% and 24%, respectively.

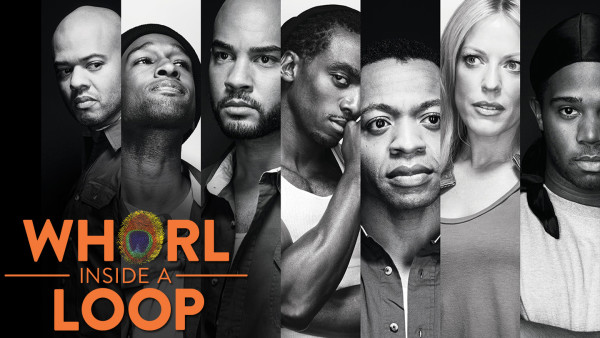

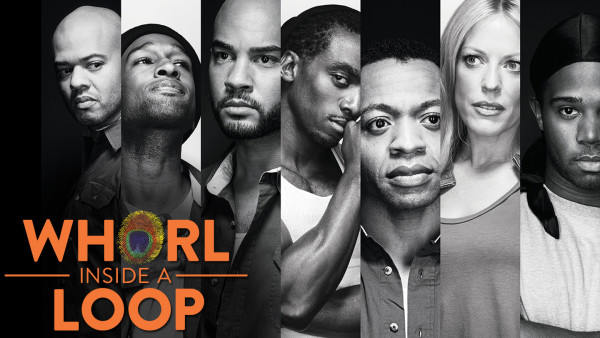

Whorl Inside a Loop, written by Dick Scanlan and Sherie Rene Scott—the first also codirects with Michael Mayer, and the latter also plays the lead—is the latest cultural work to attempt to say something about America’s prison problem. Though it only played for one month at New York’s Second Stage Theater, the one-hour-fifty-minute play has—dare I say it—left a much deeper mark, at least on your humble reviewer, than the somewhat-similarly themed straight-to-Netflix television show “Orange is the New Black” has managed to over two years with about forty hours of content. But I digress—that’s a topic for another paper.

Ostensibly, this is a play about a woman, who is a famous actress, teaching and writing a play about teaching a group of inmates about theater in a federal prison. This is an autobiographical and metatheatrical tale, written by and starring the woman whose story it depicts. The title refers to her rare fingerprint pattern, but really speaks more to the complexity of layers within and surrounding the play. Scott isn’t really the star—she thinks she is but by the end of the play she has grown and humbled. Herein lies a crucial plot point: at the beginning, she is an upper-middle-class white woman doing community service in a prison (for drunk driving and reckless endangerment) with the intent of plundering the stories—the lives—of lower-class black men doing decades in prison, most of whom if not all for crimes that were products of circumstance and environment as much as anything else. By the end, she is no longer (as) self-obsessed. I’ve seen the play, so she obviously still made it, but she ultimately did it for the men it depicts, not for herself. Again, on a surface level this play is about her, but only the densest and least self-aware audiences could leave thinking that. It must be noted that theater audiences in America—including myself and the vast majority of the audience in which I sat—are largely white. It must also be stated that the American theater audience is—if not necessarily upper-class—generally not lower-class. Scanlan, Scott, and the rest of people involved in the production are obviously aware of this. Christine Jones and Brett Banakis bring a boldly simple touch to the scenic design. There are few props—some chairs, a two-sided chalkboard, a table, and little else—which brings somewhat of a Brechtian element. Metal folding chairs line the stage and even into the aisles, leaning casually against the walls, the prison’s initials spraypainted onto the seats. This is both a classroom in a prison being used for theater and a classroom in a theater, in which the audience sits as pupils.

Besides Scanlan, there are six actors in this production, all of whom are black men. Not only do they play the six incarcerated men in Scott’s class, but the also play her (upper-class, white) various friends and family. Only Scott, whose character is listed in the playbill as “The Volunteer,” maintains the same character throughout. All six men bring immense talent to this production, but I personally was most impressed by Chris Meyers as Jeffrey and Daniel J. Watts as Flex. I won’t gave away too much of the plot, but throughout the play, each man acts out an exercise based on his life experiences—which are based on the stories of the real prisoners who inspired this play and credited as writers: Andre Kelley, Marvin Lewis, Felix Machado, Richard Norat, and Jeffrey Rivera. Meyers delivers a heart-wrenching performance, fully honoring a boy who was dragged into the “justice” system at the age of sixteen and is now thirty. Watts’ performance is the polar opposite of Meyers’ save for the passion and respect it conveys. He brings all the fire of New York in the summertime, 1977, to the stage, all the warmth, all the vibrancy of his character’s home in the Lower East Side—and then extinguishes it as he performs his arrest. Any review of this production would be remiss not to mention Derrick Baskin’s haunting performance as Sunnyside. Baskin opens the play by reading what is later revealed to be pamphlet he has prepared for the parole board directly in front of and to the audience, while the house lights are still up. This is a leitmotif at the play that becomes heavier with each recurrence, for reasons that should be obvious even if do not see the play and only read this review.

This is the story of men punished for the conditions of their environment by the society that created the same conditions. Scott’s character is called “The Volunteer” for a few reasons: she isn’t really a volunteer. She is in prison doing community service because she committed a crime that she could have avoided entirely—she voluntarily committed the crime. The men whose stories she provides a stage for had much less choice on the paths that led them to their prison. This is another aspect of her character’s naming—in reality, she volunteers her talent, her connections, her privileges as an upper-class white woman to provide space for the stories of men who need to speak and who need to be heard. I do not mean to say that she should be especially lauded for this—it is more that nothing less should be expected.

This is a very current play, though the stereotypes it seeks to shatter have been around for centuries. This is a play as much about the life and experience of Black America as it is anything else. This is a play about black tragedy; this is a play about black excellence.