The morals and ethics of genetic research and studies are placed under the microscope in Deborah Zoe Laufer’s Informed Consent, a co-production by Ensemble Studio Theater and Primary Stages. Jillian, a research scientist played by Tina Benko, is a kind-hearted mother with a die hard dedication to her work. “She never holds anything back, I love that about her,” said by Graham, her husband (played by Pun Bandhu). Her concerns for the health and well-being of her daughter inspire her to stay focused on her studies, but when given the chance of a lifetime, her ambitions lead her down a road of ethical controversy.

We find Jillian writing a letter to her young daughter Natalie. Having trouble articulating her thoughts, the chorus bounces sentences back and forth from behind the genetic anthropologist, representing the inner thoughts of a rattled mind. She starts and stops with several introductions to the letter, being disrupted by voices telling her “That’s not how she would say it.”

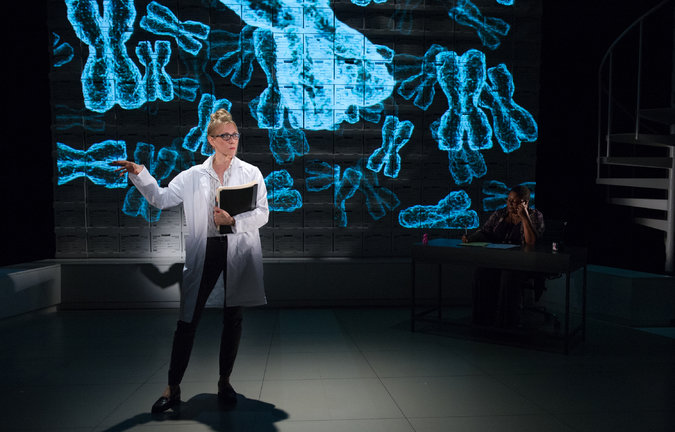

From the unfinished letter, we travel back in time to an earlier Jillian, working in the department of scientific studies at the University of Arizona. We find her rambling with glee about the magnificent capabilities of modern science. Tine Benko does an exceptional job of portraying a passionate woman with a childlike excitement for what she does. She is ecstatic to be assigned to a hands-on study of a Native American tribe in the Grand Canyon, who have been subject to a severe diabetes epidemic. Many of the tribe members can no longer walk and have severed limbs due to the disease. Led by Ken (played by a passionate Jesse J. Perez), Jillian and her team members embark on a once in a lifetime journey to research the most isolated group of humans on the planet.

There are only 670 living members of the tribe, and getting a sample of their “sacred” blood is no easy task. She must earn the trust of a hell-bent Arella (played by a brilliant Deanna Studi), the spokesperson of the tribe, in order to be granted the right to perform studies. Studi uses her strong voice and passion to support her character’s deep roots and heritage. She confidently portrays a strong woman with a genuine care for the matter at hand. The juxtaposition of Studi’s aggressive demeanor and Benko’s soft persona ads a friction that continues throughout the play. This contrast helps highlight the differences between the tribe members and the research scientist. And, while the permitted studies already put the tribe on skates, Jillian cannot help but bend their agreement to cater her personal agenda.

Beyond the permitted uses of the blood samples to do research on diabetes, Jillian digs deep into the samples in search for genetic information that may help progress her studies on Alzheimer’s, a disease that she is personally tied to. The genetic anthropologist’s mother died from the impairing disease in her thirties; not only has Jillian also contracted the disease, she fears that she has passed it on to her daughter Natalie, explaining the opening scene. Natalie only has a twenty-five percent chance of conducting the disease, but her mother will “do anything to save her”, “no matter who got hurt.”

When Jillian crosses a blurry line, she finds herself, and all of her studies, in a rapid spiral downward. Her “intentionally simple” forms of consent land the anthropologist and the entire university in an unintentionally complex predicament that might cost her this precious opportunity and her job. Jesse J. Perez and Myra Lucretia Taylor (playing Dean Hagan and a member of the chorus) do an exceptional job of expressing deep anger and disappointment in Jillian, reaching a devastating climax to the play.

The clean-cut stage designed by Wilson Chin resembles an empty laboratory, an intentionally bare environment with very few props. This brightens the spotlight and allows the cast to fabricate the environment around them, scene by scene, line by line. With good acting and stage presence, the cast of five turns the small space from a lab, to a child’s birthday party, to the crevice of the Grand Canyon, to a lab once more. This versatility allows the cast of Laufer’s play to effectively present the problem at hand.

Where a scientist sees a breakthrough, a member of a religious group might see a compromise to his or her faith. Where Jillian sees an opportunity to find a cure for both diabetes and Alzheimer’s, Arella sees an outsider taking a stab at her and her tribe’s creation stories. While the anthropologist means to do nothing but help progress the health and well-being of all people involved, she looks past the intentions of the tribe, only to see her own. Informed Consent (inspired by real events) shines light on the controversial medium between scientific discovery and religious beliefs.