Running a bit late with this by now, oops, but that seems to be the general state of affairs with me. I’ve been thinking, which apparently takes me about five times longer to do than everyone else, but… more or less since our arrival, we’ve had variations of the question “what are your impressions of China, of Chinese people?” lobbed at us. My initial-initial-right-off-the-plane impression was, “it’s [just another] place, and these are [its] people.” The first revision of that thought came about during the bus ride from the airport to our dorm, when, looking out the window, I briefly thought I had fallen asleep at the wheel on I-5 because the road signs looked familiar, only to be brought back to reality by a completely silent near-death-experience of the “large-vehicle + large-vehicle + rapidly decreasing distance between them = pain” variety: “it’s an old place with new things, and its people are crazy-hardcore drivers.”

Several other revisions along that theme have since occurred, but the one I’m currently chewing over is “it’s an old place and a young place, and its people are old and young.” While that raises questions about the relativity of age as it applies to a nation’s people as well as a nation, I’m less than qualified to have that discussion, so I’m going to share the experiences that helped give shape to (this version of) my impression of China and hope that will suffice.

First, please bask in the glory that is this amazing road sign:

This sign might be my favorite thing about China, hands down. When I first saw it I laughed and then I was confused, because I couldn’t figure out why I laughed. It’s probably not even funny unless you know someone who plays or played in the brass section of band/orchestra – and probably not funny even if you do – but I first read this sign as “no French horns allowed” and was in the middle of asking myself what China had against the French horn, of all things, when I realized it (was probably not even a French horn, apologies) wasn’t discriminating against one particular instrument. The sign means “no horns allowed, regardless of ascribed nationality.” As in, “do not honk your horn.”

That sign is hilarious just for that alone, but also because everyone who has a horn honks it (unless it’s 6 – 8AM and they are on the road right in front of a school); motorbikes, cars, bicycles… all honk. It makes for a very noisy but effective method of vehicle-vehicle and vehicle-pedestrian communication. And that’s the thing: honking is not an anger response, it’s a warning system similar to “on your left.” I’d say it’s pretty effective considering I’ve not seen any car crashes (there was a fender-bender between two BMWs in Qingdao, but that doesn’t count because they only scratched their ridiculously expensive paint jobs) and the one motorbike crash I did see happened because a pedestrian was too busy with their phone and didn’t get out of the way despite several warnings and two motorbikes swerved to avoid them.

Second, the Mid-Autumn Festival, September 27. I didn’t get any pictures of that – or rather, the one I did get was blurry and dark and a travesty to commemorative photography – but it was a pretty chill event. I’ve never been to a celebration in the U.S. so I’ve nothing to compare it to, but I think it went okay… even though we couldn’t see the moon. The College of international Exchange put on a little party in the courtyard of the international students’ dorms with tables and too many moon cakes and so much glorious fruit; Sprite, Pepsi, and Coke were provided in abundance. The Dean from our College gave a speech that I couldn’t hear over the conversations of fellow students; a teacher at our table told me to react as if I could hear him anyway, and told me (with a conspiratorial wink) that was part of Chinese culture.

We have Chinese tutors here, and after break a couple of them asked me what we did for the Mid-Autumn Festival, if we went to the celebrations at Qian Fo Mountain or something. I told them about our little party and they were surprised and a little disappointed there was no alcohol or dancing involved. One was very adamant about it, and said “That wasn’t a party! Especially since you couldn’t even see the moon.” They laughed when I told them some of the other international students left shortly after the Dean’s speech to go get alcohol, and didn’t return. So at least some people had a proper celebration.

The National Holiday began the following Wednesday, October 1, and had an official run of about a week, give or take some professors being lenient regarding attendance. We kicked off the Holiday by visiting part of the Daming Lake-Baotu Springs park area as a group. The area supposedly used to be a famous general’s estate, and the lake was originally a moat of sorts surrounding it, according to the informational signs posted around the lake’s gates. What remains of that estate – which has since also served as government buildings since the Republican Era – is now a ridiculously beautiful recreational-historical-cultural-center park.

Seriously. I spent another two days walking around Daming Lake and Five Dragon Pools (another of the spring-areas of the park) with my friend who came to visit.

It’s stunning.

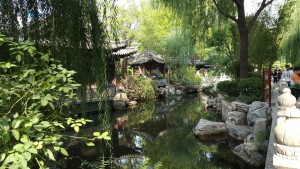

Just look at this world-renowned scenery:

(sorry)

This is a shot from inside Baotu Springs here in Jinan, which is the most beautiful spring garden area on Earth according to the Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty. When we went there as a group, I commented on this view and heard several iterations of “what a shame.” While I can see where that view comes from, I disagree. It’s not a shame; Jinan hasn’t had to completely shut down the spring due to surrounding construction, and the main water source of the spring is – as far as any of us can know – uncontaminated and fully functional. I appreciate that even as Jinan, the capital of Shandong province, has grown in population and infrastructure continues to expand, there are still ample and beautiful parks easily accessible to its citizens. I just… really appreciate that you can see something of history while looking toward the future.

One of the last things we did as a group before separating out for independent travel/research was something very difficult and very, very fun. We were immensely lucky to learn some taijishan, a form of taiji (or tai chi) called “fan dancing” from some friends of Yueping’s, a couple who have taught taiji for many years. Despite their age, they both put us to shame in terms of flexibility, mobility, and stamina. It was an honor to learn from them; their enthusiasm and knowledge were easily read by, I think, all of us, even without being able to communicate directly with them.

There are six sections to the form we began to learn, and in the two sessions we had with this couple we got through only the first three. But we’ve been practicing on our own since then, with the goal to perform for them at the end of the program as a sort of “thank you” for their time and efforts. I thought I had a photo of all of us with them, but my computer tells me that I don’t, which, rude.

I didn’t go anywhere during the independent travel time, mostly because I have been experiencing delays regarding my independent project, but also because I simply didn’t have the funds, hah. No worries, though; I walked around Jinan a lot with my friend, who stayed for a week, and had more conversations with Jinan citizens in Chinese than I had been able to have since the program began. It was fun and relaxing, and made me want to see more of China.

Partially because the question I was asked most often – and am still asked, every time I meet someone new – is “how do you find China, how do you like it?” The short answer is that I like it very much (this is also the only answer I have the vocabulary to give in Chinese, because I’m a bad student).

The more complex answer is one that I’m still working on. I don’t feel I can say, definitively, how I like China because I have only been to two cities within China – and two fairly large, increasingly-Westernized cities, at that. I know there are non-urban parts of China, and less-Westernized large cities, but I haven’t been to those places.

I know that I like what I’ve encountered of China, and that my limited experience makes me want to know more – not because “real China” has somehow blown away my preconceived notions of “China,” which everyone I’ve talked to who has been to China has said. I want to know more of China because in the U.S., we are forced to construct a very limited image of China, and I’ve always known that image couldn’t be real, because that image is basically one-dimensional and no single human being – let alone a population, a country, a nation – is one-dimensional. There are many sides to “China” and I feel like I’m finally getting to see a few of them. I like what I’m seeing, especially when it’s so different from what I’m used to in the U.S.; I like how seeing another culture, another society, gives me another lens through which to view the world as a whole, not just the places (and times) in it that I get to live.

Also, China’s just pretty great. Yeah, it could stand some improvement in certain areas – some of which Westerners know about and some of which Westerners don’t but should know about – but the cool thing is? I think that improvement is in progress. Talking to Chinese college students – graduate and undergraduate – and being around non-academically-involved Chinese makes it clear that they have similar concerns about China as their Western contemporaries: human rights, civil rights, democracy, politics… they care. That is one thing that I do want to make clear to people who haven’t been to China, that Chinese people are not passive subordinates oppressed by a lethargic and conservative Big Brother government – they find ways to talk about and criticize these things, they are finding ways to propose and effect change. It’s only a matter of time.

It’s an exciting time to be getting to know China.