Fujisan, standing at 3776 meters above sea level, is the tallest volcano in the Japan archipelago. One does not have to leave the bustling streets Tokyo to witness the grand presence of Fuji. In fact, you can find Fuji images plastered on everything from a 5-inch tall tissue box in Shinjuku (Fig.1) to a 7-foot tall hybrid mural of Hokusai’s most famous paintings of Fuji, The Great Wave and Red Fuji, at a restaurant in Asakusa (Fig.2). Fuji permeates the streets of the busiest districts of Tokyo, from tourist-packed neighborhoods such as Asakusa, Shibuya, and Harajuku to the transportation hub of Shinjuku and the high-end shopping center of Ginza. Fuji is easily recognizable regardless of how it is portrayed. Such wide-spread recognition of Fuji as the icon of Japan was established even before it was inscribed as a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage in 2013. Fuji’s status as a cultural heritage site, despite its being a natural entity, suggests its long-standing role as a subject of Japan’s cultural development.

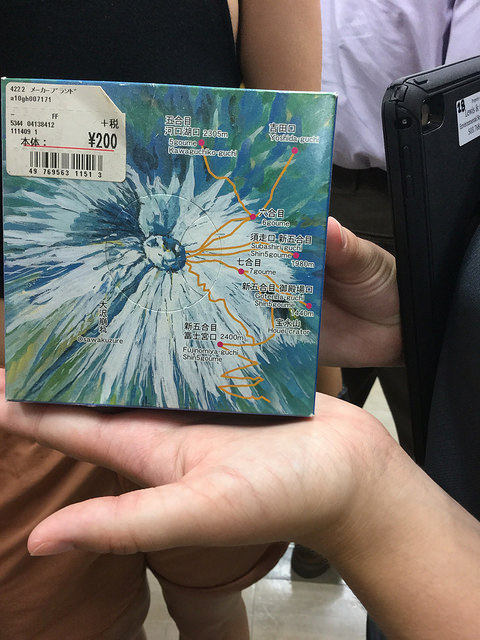

Fig. 1. A tissue box in a Shinjuku golfing store with imagery of Fuji on every side and a map on top.

Fig. 2. Hokusai hybrid wall mural in an Asakusa restaurant.

Fuji worship (Fujiko) has been an integral part of Fuji’s culture since the 12th century, when Matsudai Shōnin first climbed Mt. Fuji and founded the Murayama Shugendō cult. At that time, Fuji was established as a sacred mountain and started to attract ascetics and pilgrims to its vicinity. In the following centuries leading up to the Meiji Restoration in 1868, religious cults of Fuji prospered, and more and more believers and pilgrims visited, supporting the mountain’s local inhabitants. The persistence of numerous religious relics, worship sites, and cults (such as the Murayama Shugendō and Fusōkyo) into modern times further reinforces their crucial role in Fuji’s cultural development.

Yet, when we took to the streets of Tokyo to seek out as many representations of Fuji as possible, little of this religious significance of Fuji was felt. Most representations of Fuji that we found focused largely on its iconic shape and surrounding landscape. Photos of Fuji in its natural state serve as a scenic backdrop for posters, advertisements, etc. (Figs. 3, 4). At the same time, Fuji’s image is also stylized in paintings, illustrations, and animated caricatures as seen on artworks, souvenirs, and brand icons (Figs. 5,6). Clearly, Fuji has become an auspicious and highly commercialized item, but its popularity seems to have left behind its rich religious history.

Fig. 3. Fuji on an advertisement in Shinjuku station for a trip to Hakone.

Fig. 4. Fuji on a sushi restaurant window menu in Asakusa

Fig. 5. Mount Fuji towel line found in the window of a store in Shibuya.

Fig. 5. Mount Fuji towel line found in the window of a store in Shibuya.

Fig. 6. Fuji on a coin purse in a display case in a shop in Asakusa

These patterns within Fuji images could also be seen in Hokusai’s woodblock prints of Fuji. Besides being one of the most important figures in popularizing the image of Fuji, Hokusai was also known for his unorthodox use of Fuji as a backdrop for depictions of human life in his 36 Views of Fuji collection. Many prints in this collection are heavily popularized and duplicated for commercial use. Such famous prints such as The Great Wave and Red Fuji could easily be spotted all around the tourism-oriented streets of Asakusa (Fig. 7). Many of Hokusai’s prints also depict pilgrims and worshippers climbing the mountain. Yet, we could not find any of these pilgrim prints on the streets of Tokyo. In fact, we did not find any religious-themed illustrations of Fuji in any of the four districts we explored. This once again suggests the invisibility of Fuji’s religious representation in modern Tokyo.

Fig. 7. Red Fuji Hokusai print on umbrella at Asukusa gift shop.

Religion is becoming invisible not only in the portrayals of Fuji but also in the activities relating to the mountain. Fujizuka — replicas of Fuji that Fujiko worshippers with physical constraints could climb instead of the actual mountain — used to be popular sites for Edo inhabitants. In fact, at one point, there were over a hundred fujizuka in Tokyo. Asakusa Fujizuka, one of the most popular fujizuka of its time, is now a miniscule mound of tiles in a corner of an obscure playground (Gottardo, 7/2/17). A few other existing fujizuka continue to enjoy a small number of worshippers, separated from the buzzing streets of the capitol (Fig. 8).

Fig.8. Fujizuka at Hatanomori Hachiman Shrine in Sendagaya, Tokyo.

Despite Fujiko’s long history and crucial role in establishing Fuji as a World Cultural Heritage, its influence and presence has diminished significantly in modern Tokyo. While one can seek out Fujiko members at various fujizuka tucked away in some small corners of Tokyo, or visit the 6th descendant of the founder of Fusōkyo, one will certainly find Fuji’s religious history hard to encounter walking down the busiest streets of Tokyo.