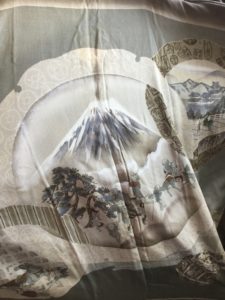

As I reflect on the depictions of Fuji we discovered in our adventures around Tokyo, a picturesque view of the illustrious mountain itself lies before me. We are currently staying at a farmhouse nestled in the tiny village of Nemba. The scenery here is breathtaking and vastly different from the busy streets and tall buildings of Tokyo. Nemba offers the real thing: an up close and personal perspective of Mount Fuji. In our quest to find representations of the mountain in Tokyo, a large portion were typically encountered on consumer products. People can purchase magnets, t-shirts, sake glasses and more that all brandish the iconic triangular shape of Fuji. I was struck by the differences in Fuji portrayals on some of the products for men versus products for women. As we browsed a pop-up shop along the streets of Harajuku selling yukata and kimono, we could only find depictions of Fuji on the yukata for men. It seemed to be singled out as a masculine design to be featured exclusively on the men’s attire rather than women’s. This trend was evident in several other kimono shops.

In contrast, for more feminine consumer items such as coin purses and tote bags, Fuji was transformed into cute, colorful patterns. These designs were more geometric and depicted Fuji in a contemporary fashion. One tote bag found in a gift shop in Harajuku even featured the mountain next to a cheerful Hello Kitty. The items portrayed Fuji as a cartoonish symbol rather than the more accurate illustrations of the mountain that we discovered on the men’s traditional yukata. Those Fuji tended to look realistic in terms of coloring and overall landscape. For me, the differences in Fuji representations on products for either men or women were quite striking.

It is worth noting that several Fuji products we encountered were not designed exclusively for a particular gender and were instead more generalized items. While a strict gender binary was not always apparent, the intended consumers are interesting to consider in light of the ambisexual nature of Mount Fuji. Throughout the religious history of Fuji worship, the mountain has been associated with several different divinities. The first deity to be linked with the sacred mountain was Sengen, a god believed to have male and female qualities. Today, Fuji is associated with Konohana Sakuya Hime. This goddess is strictly female, but there are physical elements of Fuji that are still distinguished as both male and female. In particular, tainai (womb caves) are underground lava tree molds at the base of the mountain that Fuji worship practitioners enter in order to be reborn out of Fuji. This gestation process involves features within the tainai that are believed to be corporal, such as ribs and breast-like rock formations. The womb caves are not singularly female as the name might suggest; there is also a male tainai that is used for the ritual of rebirth.

Mount Fuji continues to be characterized with ambisexual aspects, yet there are clear distinctions between some of the Fuji products for men and women. The gender differentiation I discovered in our quest to find Fuji in Tokyo can most likely be attributed to commercial motivations. Manufacturers attempt to create marketable niches by appealing to the masculinity or femininity of consumers. It is part of their business to create a consumer binary for profit, and the Fuji products we encountered are no exception. Despite the considerable differences in the depictions of Fuji and where they are found, representations of the mountain persist as a celebrated symbol of Japan in consumer culture.