For three days Michihito Watanabe, three other Lewis & Clark students, and myself trekked through the rain and blistering heat of the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen grasslands in order to collect data concerning the population of endangered butterflies within satoyama environments. Satoyama, which translates as “upland countryside,” consists “largely of second-growth environments such as grasslands, cultivated fields, coppice, and waterfront.” Satoyama environments are generally “found near and around human habitation” and are “maintained by burning and by agricultural and forestry activities” (Watanabe 2016, 25). In the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen I only encountered two or three other people. Humans were scarcer than endangered butterflies. Having previously spent considerable time in Tokyo, both grasslands felt like wilderness areas. Besides firebreaks and occasional weather instruments, there was little evidence of human interference within the two grasslands. Considering the lack of people in each area, the fact that the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen are collectively owned by entire villages is astonishing.

The entrance to the Motosukōgen grassland. Notice how overgrown it is.

These grasslands are areas known as iriaichi. In her article “Management of Traditional Common Lands (Iriaichi) in Japan,” Margaret A. McKean writes that iriaichi “are common lands with identifiable communities of co-owners, as opposed to being vast, open-access public lands used by all and in essence owned by no one” (McKean 1985, 533). Historically in iriai grasslands, villages collected thatch for roofing, fertilizer to support agriculture, and fodder to feed livestock. In forested iriai areas villages collected timber, charcoal, underbrush, fallen leaves, compost, fowl, and game (McKean 1985, 539). McKean asserts that iriai practice began between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries as villages decided among themselves the best way to cultivate and manage the essential resources harvestable from iriai lands.

Without annual burning or mowing, plant succession in Japan turns grasslands into forests (Watanabe 2016, 56). To maintain their grasslands, villages created an obligation of collective work. It was obligatory for a member of each household to assist on the day that a grassland was to be burned or mowed. Punishment was carried out for an unreasonable absence. To enforce iriai law and maintain the resources of each area, villages also employed yamami, detectives who monitored iriai lands and ensured no one was using the common land unfairly.

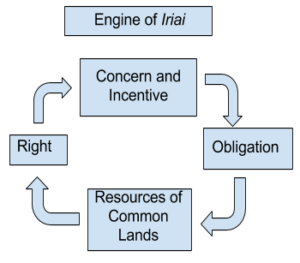

Historically, iriai lands have been maintained through a balance of right and obligation. Villagers felt a right to the resources of their common land. From their right, villagers were able to benefit personally and communally. Fueled by concern and incentive, the right villagers felt to their iriaichi led them to create obligations meant to maintain the resources of iriaichi. Obligation involved joint work and a willingness to observe iriai laws. As long as balance was maintained, the “Engine of Iriai” continued to function.

Historically, iriai lands have been maintained through a balance of right and obligation. Villagers felt a right to the resources of their common land. From their right, villagers were able to benefit personally and communally. Fueled by concern and incentive, the right villagers felt to their iriaichi led them to create obligations meant to maintain the resources of iriaichi. Obligation involved joint work and a willingness to observe iriai laws. As long as balance was maintained, the “Engine of Iriai” continued to function.

Areas like the Motosukōgen and Nojrisōgen are still iriai land even though their resources are no longer coveted and their environments are hardly maintained. The Nojirisōgen has not been maintained since 1962. The Motosukōgen is mowed annually, but only because the act of mowing ensures that its governing village is able to legally maintain its iriai rights. Over the last few decades forests have encroached upon the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen. Both grasslands have become neglected and decreased in size.

Wandering through the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen with the history of iriai land in mind was interesting. Nothing in the grasslands would have led me to assume that these areas are owned by so many people. The only people I encountered were lone butterfly collectors and I witnessed scarce evidence of human interaction in the environment. However, villages cling on to their iriai rights even as forests become overgrown and grasslands disappear. My assumption is that villagers hold on to their iriai land because of a slight hope that it might become profitable and relevant again. At the Fuji Iyashinomori Woodland Center, Haruo Saito explained that the “Engine of Iriai” no longer functions as it did in the past (July 18, 2017). Currently, villagers feel much more of a right to their land than an obligation to maintain it. In the past, the common obligation to maintain iriai land was incentivized by the resources the land could provide. However, in modern Japan locally grown thatch, fodder, and underbrush is neither profitable nor relevant. Villages are no longer dependent on the resources of their common land. Furthermore, the benefit gained from iriai land is no longer dependent upon the land’s maintenance.

The Nashigahara grassland is iriaichi that stands in contrast to the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen. The Onshirin Regional Public Organization is a well-established and highly bureaucratic association which represents the interests of all the villages that hold iriai rights over the Nashigahara. Onshirin rents the Nashigahara to the Japanese Self Defense Force which uses the grassland as a military practice zone. Because the Nashigahara is in use, it is the only grassland that is not decreasing in size. Paved roads run through it and it is burned annually. While looking for butterflies, I encountered more people in the Nashigahara than in the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen combined. In addition to military personnel, I saw people using motor bikes recreationally, collecting butterflies, and harvesting wild herbs. Like the mowing of the Motosukōgen, the burning of the Nashigahara is a symbolic gesture. By annually burning the grassland, villagers are able to maintain their collective property rights. Onshirin receives monetary benefit from leasing the Nashigahara to Japan’s military. Thus, unlike at the Motosukōgen and Nojirisōgen, the villages that hold iriai rights over the Nashigahara still benefit from the Nashigahara’s maintenance. Benefit incentives the obligation villagers feels to annually burn the Nashigahara. The Engine of Iriai functions smoother in the Nashigahara because benefit balances right and obligation.

McKean, Margaret. “Management of Traditional Common Lands (Iriachi) in Japan.” Proceedings of the Conference on Common Property Resource Management (1985): 533-589.

Saito, Haruo. Lecture at Fuji Iyashinomori Woodland Center. July 18, 2017.

Watanabe, Michihito. The Natural Features of Mount Fuji. Vol. 2. The Current Status of the Mountain’s Northern Side. Fujikawaguchiko, Japan: Mount Fuji Nature Conservation Center, 2016.