From 1998 to 2015, Portland experienced significant and continued gentrification, centered on the city center and radiating out through the streetcar suburbs of the Inner Eastside. Transit’s contribution to this gentrification is multifaceted. I consider the relationship to involve a combination of transit’s direct effects on the land/housing market and the way in which provides justification for densification and reallocation of land to its “best use.” Revitalization and urban renewal strategies in Portland are predicated on the perceived underutilization of land, on the basis of the present spatial and economic configuration of an area falling “below” its potential. Transit access is emphasized as an integral aspect of the potential of an area. Though revitalization planning documents usually claim to aim and plan for improved circumstances for existing residents, the logic of allocation of land as a commodity and the scarce funding available for affordable housing ensures that where revitalization succeeds, displacement follows. These plans are not always “successful,” however, and a deeper investigation into why transit’s influence on gentrification is mediated by geography is warranted. Simple proximity to downtown seems to play a large role in laying the ground for gentrification, though even after accounting for this variable, the differential experience of transit-adjacent urban renewal zones in East Portland and those in North Portland reveals that there are other factors at play.

The core-centric nature of increases in socioeconomic status and land value appreciation means that the areas best served by transit have increasingly become class-exclusive neighborhoods. This raises a potential contradiction in equity—those who benefit from transit those most may be displaced by its provision within a hot housing market. We can see some of the effects of this contradiction through a comparison of the density of the frequent transit network and the percent of residents commuting on transit. There is also the potential for a disconnect between the use value of transit and its signaling value. This signaling value involves both how transit overlaps with and indicates pre-war urban form, walkability, and relatively mixed zoning, and how transit investment is used as a municipal tool to signify commitment to an area (to varying degrees of effectiveness).

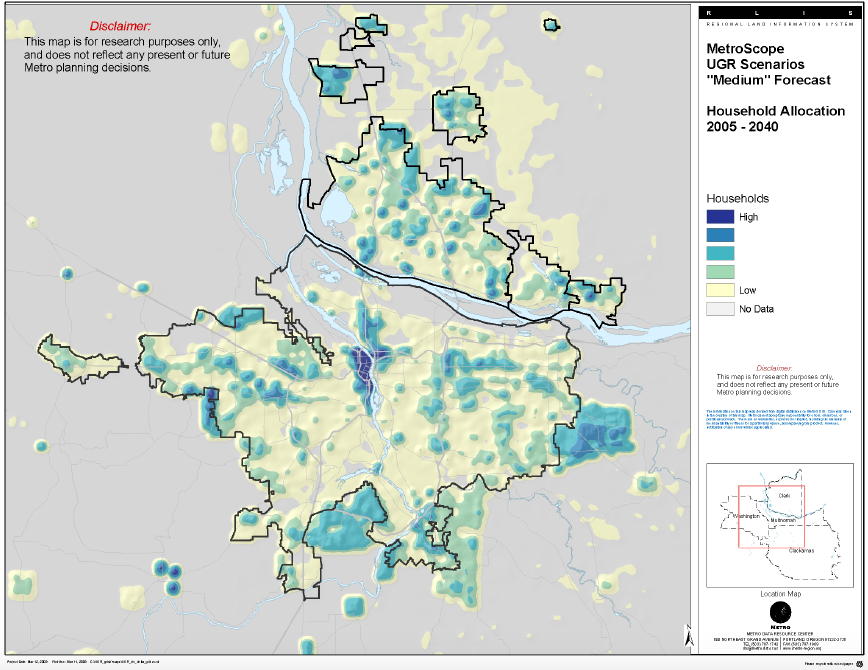

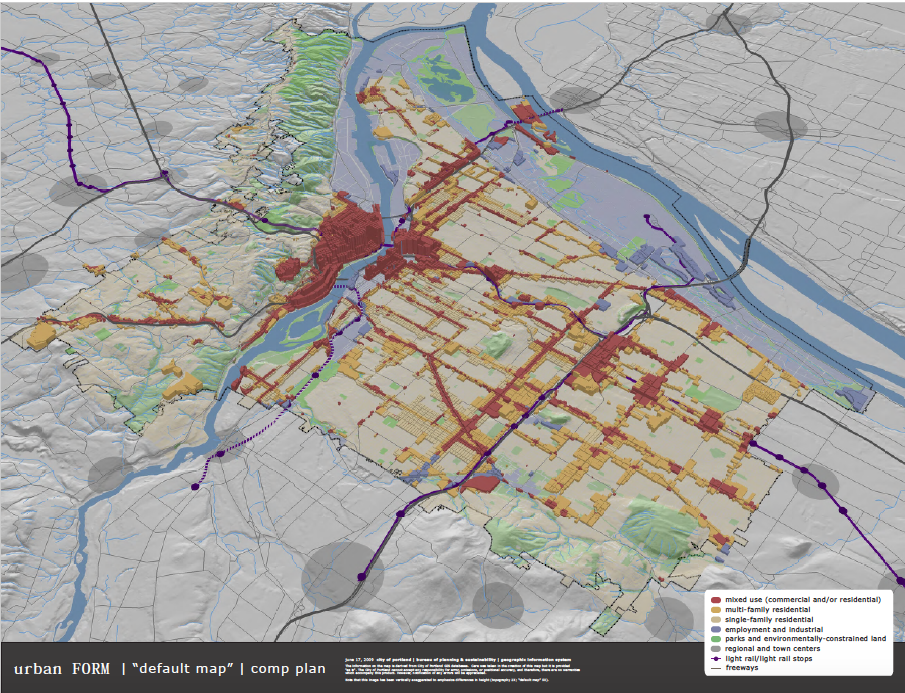

There is a mismatch between the landscape of appreciation-gentrification and where the city expects to see population growth in the Comprehensive Plan, especially in inner Southeast and Northeast Portland. This reflects the extent to which historically white areas of Portland’s Inner Eastside have been able to codify privilege in zoning laws and protect their neighborhoods from substantial up zoning. North and East Portland both see significantly larger areas of multifamily zoning and allowable density, extending relatively far from frequent transit nodes, while Southeast and Northeast Portland have predominately single family zoning within a block of transit corridors and light rail stations. Even those corridors in the Inner Eastside which allow densification are extraordinarily contested, as illustrated by the current uproar over since proposed development on SE Belmont St. The city’s strategy of densification along transit is thus likely circumscribed by the relative influence of existing and past residents. This resistance by the middle class to development deepens the contradictions in equity, contributing to the outward spread of gentrification by constraining housing supply in some of the most desirable areas of the city.

There is reason to believe that these results are broadly applicable and relevant. Portland is comparable in size, historic urban growth patterns (streetcar suburbs), and present day growth to many mid-sized North American cities. Sustainability discourse has become rather dominant in urban planning; as one of the earliest adopters and most prominent proponents of transit-oriented green growth the experiences of Portland provide an indication as to the general effects of this revitalization model. It should also be noted that gentrification is a generalized phenomenon precisely in the American metros ranked as having the best transit and having the largest areas of walkable, prewar urban form. The relation between transit, land value, and gentrification is of critical importance to understanding the contemporary city and areas of contradiction under neoliberal urbanism.