Note: Some links on this page may be to archived resources.

Though they are potentially useful, they are not fully functional.

The challenge

Environmental programs are among the most cross-disciplinary in higher education, drawing upon concepts and skills from the physical and life sciences, social and behavioral sciences, and arts and humanities. This makes our work exciting…and challenging! It is easy for interdisciplinarity to become a mess…and for the word to become meaningless, in spite of helpful work like Nissani (1995), a readable paper likening interdisciplinarity to a fruit salad and recommending four criteria for its quality: the number of disciplines, distance between them, novelty, and integration.

One illustration of interdisciplinarity draws upon the famous south Asian tale of the blind sages and the elephant, in which each sage understands but a part of the whole. This presents two challenges for environmental scholarship (Proctor et al. 2013): inclusivity, or making sure all the parts are included, and coherence, or making sure these parts are assembled correctly. The diagrams* below, reflecting this famous tale, suggest what would result if we don’t pay attention to both.

*Original image credits Jason Hunt

Interdisciplinarity as weaving

Let’s think of doing interdisciplinary environmental scholarship as weaving a broad range of processes and perspectives (inclusivity) in a manner faithful to reality (coherence). We can examine each of these steps in order.

1. Inclusivity

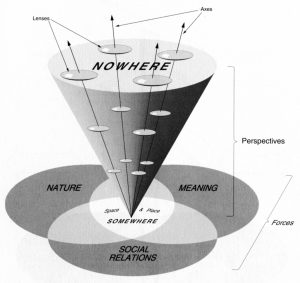

Inclusivity means many things in environmental higher education, including the important movement to promote diversity and inclusion. Here, we are thinking of disciplinary and hence topical inclusivity: one measure of inclusivity that resonates with our situated approach to environmental research draws upon geographer Robert Sack’s application of the notion of place to human-environment interaction (Sack 1990; 1992). To Sack, reality mixes forces of nature, social relations, and meaning; it also involves perspectives (views from somewhere vs. nowhere). To these forces and perspectives, we can add two resultant realities: hybrid objects (e.g., agriculture) and places (e.g., forests).

We can place a wide array of environmentally-significant topics under these six categories [as our ENVS Program once did via a glossary of bibliographic resources on over 75 topics, now archived—see also here for topics by category]:

- Nature: Topics primarily involving biological, chemical, geological, and other processes shaping a place as understood via the natural sciences.

- Social relations: Topics primarily involving economic, political, social, and other processes shaping a place as understood via the social sciences.

- Meaning: Topics primarily involving aesthetic, cultural, historical, and other processes shaping a place as understood via the arts and humanities.

- Hybrids: Objects that mix processes of nature, social relations, and meaning in place-specific ways.

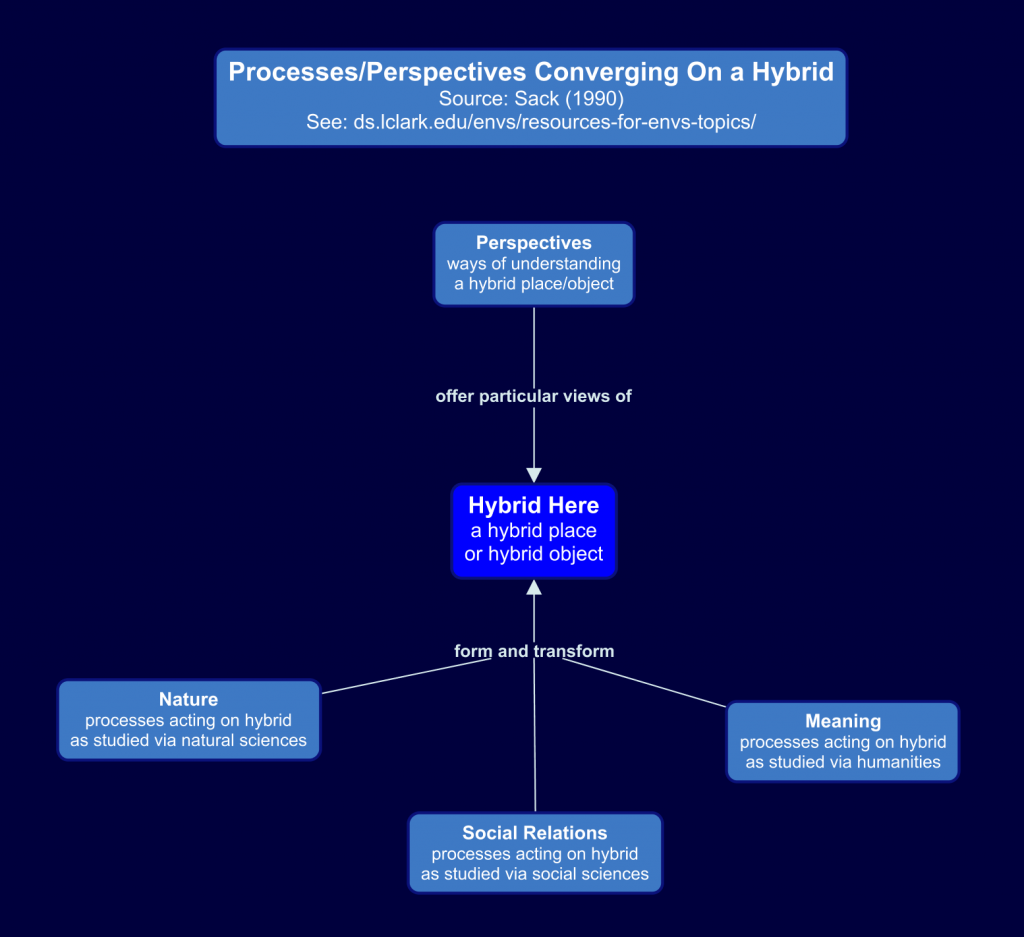

- Places: Gatherings of processes (“forces” in Sack’s diagram) and perspectives, as grounded in one or more geographical locations.

- Perspectives: Ways of knowing (e.g., a place), broadly spanning views from somewhere (local, contextual) to views from nowhere (global, universal).

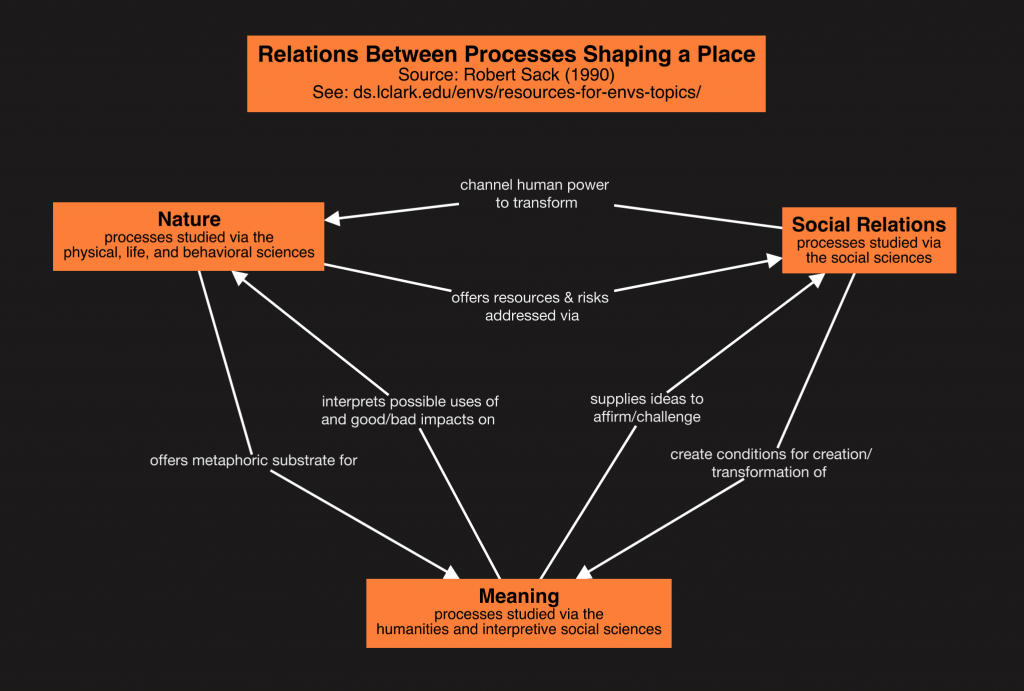

Nature, social relations, and meaning are disciplinary categories representing common divisions of scholarship into natural sciences, social sciences, and arts & humanities. As Sack’s diagram suggests, however, reality comes at us in a hybrid, mixed-up manner, where nature, social relations, and meaning mix in the situated context of particular places, and are understood via a range of perspectives.

Following this sixfold taxonomy, inclusivity would then be suggested by scholarship that dips into as many of these six categories as possible—or, as another way to think of it, scholarship that dips seriously into nature, social relations, and meaning, and the divergent perspectives of interest to each, applying these four categories to hybrid objects or places (the other two categories).

2. Coherence

But how shall we assemble these topics in a coherent manner? It’s not enough simply to list a bunch of topics (i.e., multidisciplinarity); we must relate them in meaningful ways that reflect reality (i.e., interdisciplinarity). Here are three slightly different concept mapping possibilities [derived from an earlier digital scholarship resource for our students, now archived] that may help:

- One you may already be familiar with involves mapping actors and processes as an ANT Cmap. Following actor-network theory (e.g., Venturini 2010), you could start by listing a wide range of specific actors related to a particular environmental issue, place, or hybrid object, then you would create a box (concept or noun) for each actor and draw/label lines (proposition or verb) showing how they relate—bearing in mind that relations define actors in ANT! Actor-network theory has been applied to a broad range of contemporary topics and issues; for background, see here, and for a help page see here. Typically, though, we are mapping specific actors in an ANT Cmap, not general topics—thus the below options may be more applicable.

-

Nature/social relations/meaning When you weave topics, it’s important to realize that different actors play different roles in an interdisciplinary issue. Many times you are trying to weave together topics representing processes of nature, social relations, and meaning: this diagram offers general guidance on how these realms relate. Sack argued that places are a mixture of processes drawn from all three realms, and each acts on the other as suggested here. Your specific topics may well reflect these general relations: just create a box (concept) for each of your topics, then add/label lines (propositions) showing how they relate. This example is much like an ANT Cmap in that there is no concept in the middle: rather, each concept is one of your topics. Remember that interdisciplinarity is achieved via choosing multiple topics spanning these realms, then weaving them together in creative ways.

-

Hybrid object/place If you are considering a hybrid (object) or place, the three categories of processes above, plus one or more perspectives, broadly come together as in this diagram (or see Sack’s original diagram). A hybrid object may be a general topic listed under hybrids in our ENVS topics glossary [archived site resource], or may be a specific object—we once used the text Environment & Society for ENVS, which introduced a wide range of hybrid objects ranging from lawns to wolves. A place, as suggested via Sack (1992; see also Proctor 2016) is inherently hybrid, as it gathers processes and perspectives from a wide range of scales in space and time. (And remember that hybrid objects circulate via places!) As you’ll see in this general diagram, hybrids arise from processes of nature, social relations, and meaning, and are interpreted via one or more perspectives. Your specific object or specific place will, then, include particular processes and perspectives, acting as in this diagram. Note that this Cmap indeed has a concept in the middle: this is your hybrid object or place, then contributing topics are arrayed around and connected to it.

Concept mapping simply helps you visualize connections; you must still communicate these connections, via text, equations, or other means (certainly including your Cmap!). But concept mapping may help you approach interdisciplinary environmental issues in a manner that reflects both inclusivity and coherence—if so, you are well on your way toward offering interdisciplinary expertise in understanding and addressing these issues.

Weaving an area of interest

In our ENVS Program we long required that students propose and defend a concentration. More broadly, you may wish to define an area of interest in your environmental scholarship. The notes below, derived from our guidance toward weaving interdisciplinary concentrations, may help you as you define your own inclusive/coherent area of interest.

- As noted above, the first step is to choose an inclusive set of environmental topics. By “inclusive,” see the note above suggesting that a good distribution across the six topic categories, vs. all topics being in one category, will help your area of interest become richer and more relevant.

-

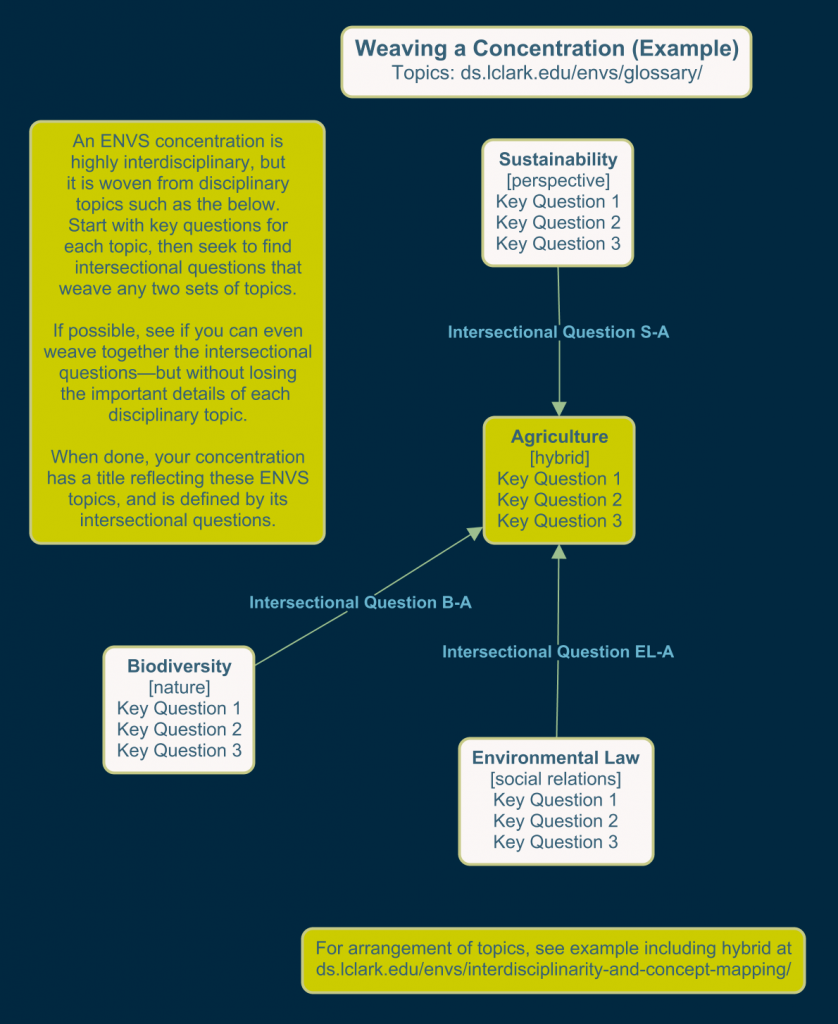

Weaving a concentration Now, how to weave these topics in a coherent manner? See the concept map at right illustrating the general process. Here is the general step-by-step:

- Make sure you are clear as to the role each of your topics will play, as a function of its category. For instance, a topic from the nature category will address key questions for which natural science concepts and skills offer insight, whereas a topic from the hybrids category addresses questions that mix the nature, social relations, and meaning categories, and a topic from the perspectives category address questions about a particular view or way of approaching your emerging concentration theme. So, the role played by topics in these three categories is quite particular.

- Arrange your topics on a Cmap as per their categories (roles). See the hybrids Cmap above, where nature, social relations, and meaning are arrayed toward the bottom, perspectives at top, and hybrids or places in the middle (at the intersection of the other categories, given their hybrid character). This will help you remember which role each topic plays in your resultant concentration theme.

- Include key questions (or quick summaries to save space) in each topic concept (box). You don’t want to lose your sense of what is key to each field as you mix them!

- Now, generate intersectional questions that connect your topics, specifically by relating one or more key questions from each topic. These intersectional questions are among the key questions of your emerging concentration theme. You may even find connections between some of these intersectional questions!: if so, link them with an integrative question.

- The title of your resultant area of interest will reflect some creative combination of the topics you wove into it Congratulations!

References

-

Nissani, Moti. 1995. “Fruits, Salads, and Smoothies: A Working Definition of Interdisciplinarity.” The Journal of Educational Thought (JET) / Revue de La Pensée Éducative 29 (2): 121–28.

- Proctor, James D., Susan G. Clark, Kimberly K. Smith, and Richard L. Wallace. 2013. “A Manifesto for Theory in Environmental Studies and Sciences.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 3 (3): 331–37. doi:10.1007/s13412-013-0122-3.

- Proctor, James D. 2016. “Replacing Nature in Environmental Studies and Sciences.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 6 (4): 748–52. doi:10.1007/s13412-015-0259-3.

- Sack, Robert D. 1990. “The Realm of Meaning: The Inadequacy of Human-Nature Theory and the View of Mass Consumption.” In The Earth as Transformed by Human Action: Global and Regional Changes in the Biosphere over the Past 300 Years, edited by Billie Lee Turner, William C. Clark, Robert W. Kates, John F. Richards, Jessica T. Mathews, and William B. Meyer, 659–71. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

-

Sack, Robert David. 1992. Place, Modernity, and the Consumer’s World: A Relational Framework for Geographical Analysis. Johns Hopkins University Press.

-

Venturini, T. 2009. “Diving in Magma: How to Explore Controversies with Actor-Network Theory.” Public Understanding of Science 19 (3): 258–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662509102694.