The challenge

Environmental studies is one of the most interdisciplinary fields around, including concepts and skills drawn from the physical and life sciences, social and behavioral sciences, and arts and humanities. This makes our work in ENVS exciting…and challenging! It is easy for interdisciplinarity to become a mess.

One illustration of interdisciplinarity draws upon the famous south Asian tale of the blind sages and the elephant, in which each sage understands but a part of the whole. This presents two challenges for environmental studies (Proctor et al. 2013): inclusivity, or making sure all the parts are included, and coherence, or making sure these parts are assembled correctly. The diagrams below, reflecting this famous tale, suggest what would result if we don’t pay attention to both.

Weaving interdisciplinarity

Let’s think of doing interdisciplinary environmental studies as weaving a broad range of processes and perspectives (inclusivity) in a manner faithful to reality (coherence). Here’s one way to do this:

- Start by choosing topics of relevance to an environmental issue, making sure to choose enough so as to be inclusive.

- Then weave these topics together in a coherent manner using tools such as concept mapping—with text explaining and extending your concept map.

I. Inclusivity

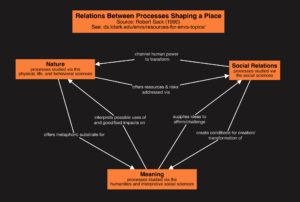

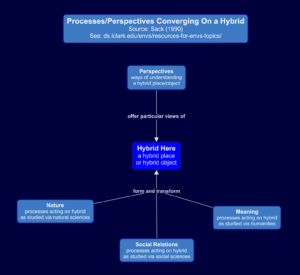

One measure of inclusivity draws upon Sack (1990) and our elaboration here, including process categories of Nature, Social Relations, and Meaning, categories of Hybrids [objects] and [hybrid] Places, and a category of Perspectives—six total (capitalized to be clear below). To the extent that you can draw upon topics from all three process categories (e.g., not only from Social Relations), one or more rich perspectives (e.g., political ecology), and apply them in the context of Hybrids (e.g., agriculture) and/or Places (e.g., forests), you are definitely being inclusive!

II. Coherence

But how shall you assemble these topics in a coherent manner? It’s not enough simply to list a bunch of topics (i.e., multidisciplinary); we must relate them in meaningful ways that reflect reality (i.e., interdisciplinary). Here are three slightly different concept mapping possibilities that may help:

- The first is not entirely related, but one you may already be familiar with: mapping actors and processes as an ANT Cmap. Following actor-network theory, you would start by listing a wide range of specific actors related to a particular environmental issue, place, or hybrid object, then you would create a box (concept or noun) for each actor and draw/label lines (proposition or verb) showing how they relate. Actor-network theory has been applied to a broad range of contemporary topics and issues; for background, see here, and for our ENVS help page (including some great examples), see here. Typically, though, you are mapping specific actors in an ANT Cmap, not general topics—thus the below options.

- When you weave topics, it’s important to realize that different actors play different roles in an interdisciplinary issue. Many times you are trying to weave together topics representing processes of Nature, Social Relations, and Meaning: this diagram offers general guidance on how these realms relate. Sack argued that Places (and, we could add, Hybrids as objects, which always circulate via Places) are a mixture of processes drawn from all three realms, and each acts on the other as suggested here. Your specific topics may well reflect these general relations: just create a box (concept) for each of your topics, then add/label lines (propositions) showing how they relate. This example is much like an ANT Cmap in that there is no concept in the middle: rather, each concept is one of your topics.

-

Hybrid object/place If you are considering a Hybrid (object) or Place, the three categories of processes above, plus one or more Perspectives, broadly come together as in this diagram (or see Sack’s original diagram). A hybrid object may be a general topic listed under Hybrids in our ENVS topics glossary, or may be a specific object—we once used the text Environment & Society for ENVS, which introduced a wide range of hybrid objects ranging from lawns to wolves. A place, as suggested via Sack (1990; see also Proctor 2016) is inherently hybrid, as it gathers processes and perspectives from a wide range of scales in space and time. (And remember that hybrid objects circulate via places!) As you’ll see in this general diagram, Hybrids arise from processes of Nature, Social Relations, and Meaning, and are interpreted via one or more Perspectives. Your specific object or specific place will, then, include particular processes and perspectives, acting as in this diagram. Note that this Cmap indeed has a concept in the middle: this is your hybrid object or place, then contributing topics are arrayed around and connected to it.

Concept mapping simply helps you visualize connections; you must still communicate these connections, via text, equations, or other means (certainly including your Cmap!). But concept mapping may help you approach interdisciplinary environmental issues in a manner that reflects both inclusivity and coherence—if so, you are well on your way toward offering interdisciplinary expertise in understanding and addressing these issues.

Weaving concentrations

Your ENVS concentration is highly interdisciplinary as well, and a slight modification of the above may help you arrive at your concentration theme, derived from a creative weaving of the core ENVS topics you selected.

- As noted above, the first step is to choose an inclusive set of ENVS topics. By “inclusive,” see the note above suggesting that a good distribution across the six topic categories, vs. all topics being in one category, will help your concentration become richer and more relevant to ENVS.

-

Weaving a concentration Now, how to weave these ENVS topics in a coherent manner? See the concept map at right illustrating the general process. Here is the general step-by-step:

- Make sure you are clear as to the role each of your topics will play, as a function of its category. For instance, a topic from the Nature category will address key questions for which natural science concepts and skills offer insight, whereas a topic from the Hybrids category addresses questions that mix the nature, social relations, and meaning categories, and a topic from the Perspectives category address questions about a particular view or way of approaching your emerging concentration theme. So, the role played by topics in these three categories is quite particular.

- Arrange your topics on a Cmap as per their categories (roles). See the hybrids Cmap above, where Nature, Social Relations, and Meaning are arrayed toward the bottom, Perspectives at top, and Hybrids or Places in the middle (at the intersection of the other categories, given their hybrid character). This will help you remember which role each topic plays in your resultant concentration theme.

- Note: Remember from the concentration instructions that your concentration theme may be, but doesn’t have to be, explicitly situated. If one of your important ENVS topics is in the Places category, however, your concentration will be situated in that broad context! Remember this as you proceed.

- Include key questions (or quick summaries to save space) in each topic concept (box). You don’t want to lose your sense of what is key to each field as you mix them!

- Now, generate intersectional questions that connect your topics, specifically by relating one or more key questions from each topic. These intersectional questions are among the key questions of your emerging concentration theme. You may even find connections between some of these intersectional questions!: if so, link them with an integrative question.

- Your concentration title will reflect some creative combination of the ENVS topics you wove into it, and the summary and questions that define your concentration will derive from the intersectional questions you identified. Congratulations!

References

- Proctor, James D., Susan G. Clark, Kimberly K. Smith, and Richard L. Wallace. 2013. “A Manifesto for Theory in Environmental Studies and Sciences.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 3 (3): 331–37. doi:10.1007/s13412-013-0122-3.

-

Proctor, James D. 2016. “Replacing Nature in Environmental Studies and Sciences.” Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 6 (4): 748–52. doi:10.1007/s13412-015-0259-3.

-

Sack, Robert D. 1990. “The Realm of Meaning: The Inadequacy of Human-Nature Theory and the View of Mass Consumption.” In The Earth as Transformed by Human Action: Global and Regional Changes in the Biosphere over the Past 300 Years, edited by Billie Lee Turner, William C. Clark, Robert W. Kates, John F. Richards, Jessica T. Mathews, and William B. Meyer, 659–71. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.